How was it okay for Hulu to retell Pamela Anderson’s incredibly personal story without her permission?

By Sarah Finnan

30th Jan 2023

30th Jan 2023

Pamela Anderson has already lived through the experience of having a private sex tape leaked. Why is it legally or ethically acceptable for her name and likeness to be used to rehash this painful moment, especially if she doesn't want it to be?

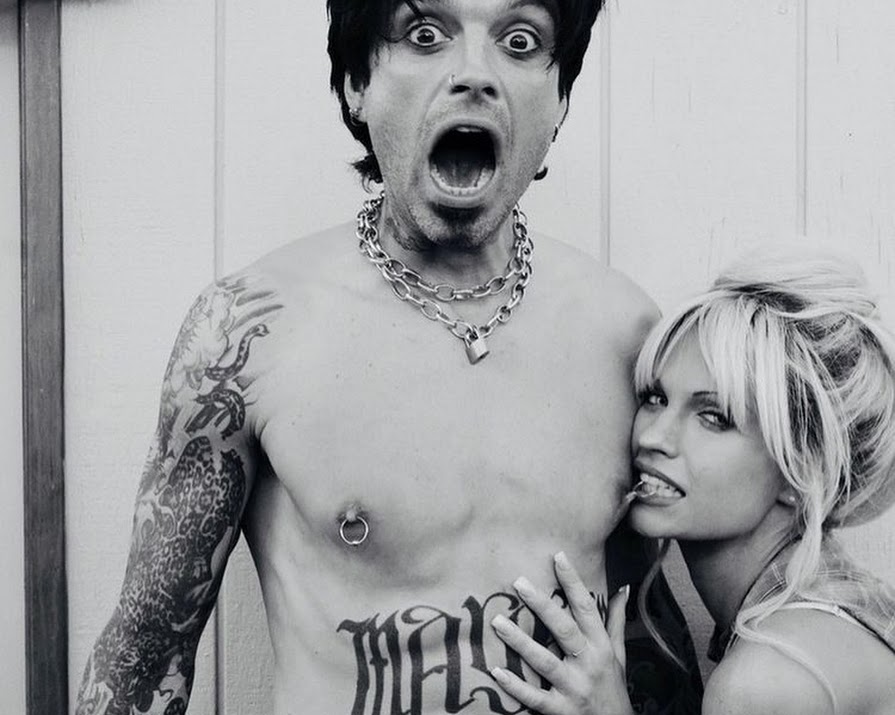

Pam & Tommy had its worldwide premiere last year… without Pamela Anderson’s permission. Refusing to give the show her blessing or be involved in any way, the show somehow still went ahead and a few months later, Hollywood was rehashing Anderson’s very personal story for the world once again.

Last year, the Baywatch star announced that she’d be releasing her own documentary to set the record straight. However, with interest in the pop-culture icon at an all-time high again, I can’t help but feel that the Hulu series did the very thing it was supposedly trying to condemn; exploit Pamela Anderson (again).

The re-exposure of Pamela Anderson

Interest in the new eight-part mini-series was initially sparked by leaked photos of actress Lily James’ incredible transformation into Ms Anderson (which took no less than four hours in hair and make-up every single day). Public outrage that she had been cast as the lead dissipated overnight and many still can’t believe the likeness between the two women. However, excited as the public may have been by James’ involvement, Anderson was decidedly less so and had absolutely no desire for the modern re-telling to happen at all.

How could Hulu make a series about Pamela Anderson’s life without her permission then? And more importantly, without her sign-off, why would they want to? Ownership in the public domain is a very grey area – one that tends to confuse more than it enlightens. There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to what celebrities have claim to, and more often than not, they don’t really have any rights at all.

As one scholarly article puts it, the widely accepted belief in the “right to know” generally overrides public figures’ right to privacy in the US and so big production companies can make programmes about famous people’s lives whether they like it or not. It happened in American Crime Story when Ryan Murphy made an entire season about the assassination of Gianni Versace without the family’s permission. It happened in House of Gucci when Lady Gaga took on the role of Patrizia Reggiani without consulting her offscreen namesake. The Queen wasn’t required to sign off on The Crown and Elizabeth Holmes didn’t approve the casting of Amanda Seyfried to play her either.

Most recently, it happened with Pamela Anderson, who never extended her blessing for Pam & Tommy to go ahead. Only this time it wasn’t about a murder, or a nearly century-long role in public life, or one of the biggest fraud cases Silicone Valley has ever seen, but a deeply traumatic and personal moment in one woman’s life – a very private moment that was made very public.

In one of her first interviews about the series, James admitted that she wished things “had been different”. “I was really hopeful that she [Pamela Anderson] would be involved,” she said at the time. “My sole intention was to take care of the story and play Pamela authentically.” She even reached out to Anderson independently, keeping the faith that they would be in touch right up until filming started.

No one in Camp Anderson was happy about the series though. Close friend Courtney Love also condemned the project, describing it as “so f*cking outrageous” and castigating those involved for making Pam relive one of the most distressing times in her life. “The tape destroyed my friend Pamela’s life,” she wrote on Facebook (now Meta). “My heart goes out to Pammy. Further causing her complex trauma. Shame on Lily James, whoever the f*ck she is.”

In the 1990s Anderson and her then-husband Tommy Lee had their LA home robbed and a private video, filmed by the couple while on their honeymoon, was republished for mass consumption and profit. And then, Hulu sold that story for mass consumption and profit. Even if that’s legally considered fair game, is that ethically okay?

Much like Hulu’s rapid-fire documentary that came out a mere month after Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival tragedy (where 10 people were crushed to death), don’t events – whether public or private – deserve to be treated with empathy, kindness and no small amount of hindsight before they’re ready to be evaluated? Otherwise, it’s just cashing in on the cultural shock value and reopening wounds that victims and their families are still attempting to sew up. If Pamela Anderson doesn’t want that part of her life retold for the world to witness (again), doesn’t she have that right to her own story? And if not, what purpose does the retelling serve? Entertainment?

For some, the Hulu series may be the first they heard of the Baywatch star, her ex-husband or their infamous sex tape. Those viewers were either too young to know what was happening at the time or hadn’t even been born yet. But, what they didn’t know before, they soon did. For others – those who were around to see the scandal play out as it happened – the mini-series just refreshed the details. They probably had a vague memory of what went down, but there were a few gaps to fill in; ones which Lily James and Sebastian Stan (who played Tommy Lee) ultimately helped to piece together.

The internet introduced us to the idea that just about whatever information we want is within our reach. It’s all readily available online and so privacy becomes obsolete. There’s a sense that once something is out there, that’s it, it’s fair game. You didn’t want us to see that? Oh, too bad. Add celebrity status or some sort of public persona to the mix, and you can pretty much count discretion out of the equation altogether. The general sentiment being that that’s the price you pay for the life you choose to live.

Emily Ratajkowski and ownership of your image

Of course, this is something that model Emily Ratajkowski has touched on before too – first with an essay she penned for The Cut and more recently in her new book, My Body.

Entitled Buying Myself Back: When does a model own her own image?, the former appeared onsite last September and predominantly explored the issue of ownership. Spurred to speak out after several different incidents in which her own likeness was used without her distinct permission, Ratajkowski has quite a full envelope of receipts to pull from.

In 2019 she was sued for reposting a paparazzi photo of herself. Five years earlier, an image from her personal Instagram account was blown up, printed on an oversize canvas, and featured in Richard Prince’s “Instagram Paintings” exhibition. “It felt strange that a big-time, fancy artist worth a lot more money than I am should be able to snatch one of my Instagram posts and sell it as his own,” she mused. The “painting” retailed for $80,000… much more than Emily wanted to spend, and even then, the idea of buying an image of herself back struck her as abnormal.

“It seemed strange to me that he [her then-boyfriend] or I should have to buy back a picture of myself – especially one I had posted on Instagram, which up until then had felt like the only place where I could control how I present myself to the world, a shrine to my autonomy.”

At 22, she found herself the unwilling subject of an internet phishing scam and private nude photos she had taken of herself were released to the world. Again, without her consent. If there’s one thing EmRata has learned over the years it’s that neither her image, nor her reflection are really her own. “I guess this comes with the territory of being a public persona,” her mother’s ex-husband once said to her over text.

In 2012, she went to photographer Jonathan Leder’s house in the Catskills where he shot a series of polaroids of her. Only a handful of images – out of hundreds – were included in the magazine shoot… the others, Jonathan published in his first book, Emily Ratajkowski, years later. Leder had no rights to the images beyond their agreed-upon usage, but one forged signature later and he had a gallery show on the Lower East Side to promote the book. The New York Post headline for the show read “Emily Ratajkowski doesn’t want you to see this art show”. So naturally, people went anyway. “The next day, my lawyer informed me, on yet another billable call, that pursuing the lawsuit, expenses aside, would be fruitless. Even if we did ‘win’ in court, all it would mean was that I’d come into possession of the books and maybe, if I was lucky, be able to ask for a percentage of the profits. ‘And the pictures are already out there now. The internet is the internet,’,” her lawyer told her rather matter-of-factly.

The book sold out and was subsequently reprinted once, twice, and then three times. Ratajkowski accused Leder of using and abusing her image for profit but the public was unbelieving. “Using and abusing?,” one questioned. “This is only a case of celebrity looking to get more attention. This is exactly what she wants.” “ You could always keep your clothes on and then you won’t be bothered by these things,” another woman wrote.

Think of her what you will, but is being subject to such blatant disregard for her bodily autonomy really the cost of beauty?

Consent

Explicit consent is another grey area on the celebrity privacy spectrum. Which brings us to Versace and Gucci; two luxury brands that have more than nationality and fashion in common. Five years ago, the Versace family found themselves the central storyline of Ryan Murphy’s American Crime Story… very much against their will. They didn’t approve of the project and they certainly didn’t want it to go ahead. “The Versace family has neither authorised nor had any involvement whatsoever in the forthcoming TV series about the death of Mr Gianni Versace,” the brand said in a statement to People Magazine at the time. “Since Versace did not authorise the book on which it is partly based nor has it taken part in the writing of the screenplay, this TV series should only be considered as a work of fiction.”

Their main reasons for opposing the series so vehemently were twofold; one, the family were wary that Ryan would focus on Gianni’s sexuality and partnership with Antonio D’Amico, and two, they didn’t want to glamorise Versace’s murder. Naturally, the show did both and Ryan Murphy proceeded with plans regardless of what the family did or didn’t want. The world was already familiar with Versace’s life story and so he could bypass the formalities of asking permission and just do it anyway.

The same happened two years ago with the House of Gucci movie. Slamming the Ridley Scott project on more than one occasion, the heirs of Aldo Gucci said that they were “disconcerted” with what they claim to be an inaccurate portrayal of events. “The production of the film did not bother to consult the heirs before describing Aldo Gucci – president of the company for 30 years [played by Al Pacino in the film] – and the members of the Gucci family as thugs, ignorant and insensitive to the world around them,” a statement from the family said. “This is extremely painful from a human point of view and an insult to the legacy on which the brand is built today,” it continued. Most of their other grievances were to do with appearances – which Forbes states is what “matters most” in the world of fashion.

Patrizia Reggiani was arguably even more displeased and denounced Lady Gaga for agreeing to play her in the movie without ever consulting her first. Gaga had her reasons of course and said that she wasn’t interested in forming an opinion based on the bias of others – including that of Reggiani herself. “I only felt that I could truly do this story justice if I approached it with the eye of a curious woman who was interested in possessing a journalistic spirit so that I could read between the lines of what was happening in the film’s scenes,” she told British Vogue, later adding, “nobody was going to tell me who Patrizia Gucci was. Not even Patrizia Gucci.”

She didn’t meet or talk with Patrizia Gucci, nor did she read the book that the movie script was based on – The House of Gucci: A Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed. “I did not want anything that had an opinion that would colour my thinking in any way,” Gaga admitted. Famous for her very method approach to taking on a new role, Gaga clearly has a system that works for her, but not meeting with Patrizia did seem like a missed trick. How could she – or Lily James, for that matter – comfortably play a character she knows doesn’t want her to do so?

As is the case with all of the above examples, so much history was already known about Reggiani, Gucci, and the notorious murder-for-hire scheme the former cooked up, and so consent was never really an issue at all.

It does feel a bit icky though. Perhaps slightly less so in the case of Reggiani, a convicted murderer, but definitely in terms of Pamela Anderson – whose story revolves around privacy and what happens when that is breached. Dredging up old memories from the past seems completely without purpose when the series’ namesakes have openly besmirched it.

Does anyone really have claim to their stories, images, and person? We might previously have said yes, but the world of celebrity documentaries and dramatised non-fiction, would make you question otherwise.