David Woodland Photography

Natasha O’Brien: ‘I want the silent victims to get the same justice that I did’

In the aftermath of Cathal Crotty’s resentencing in the Court of Appeal, Sarah Gill sat down with Natasha O’Brien to talk advocacy, the pursuit of justice and healing from trauma.

Two and a half years ago, on 29 May 2022, Natasha O’Brien was violently attacked on the streets of Limerick city for asking a young man to stop hurling homophobic abuse at a passerby. She was left with a broken nose and a concussion, knocked unconscious in an assault that only ended when someone else intervened.

Her attacker Cathal Crotty, who was at the time a member of the Irish Defence Force, seemed to feel proud of this unprovoked attack, bragging about it to his friends on Snapchat saying: “Two to put her down, two to put her out.” When approached by Gardaí, he attempted to deny any involvement, but when confronted with CCTV evidence and the Snapchat message, Crotty pled guilty.

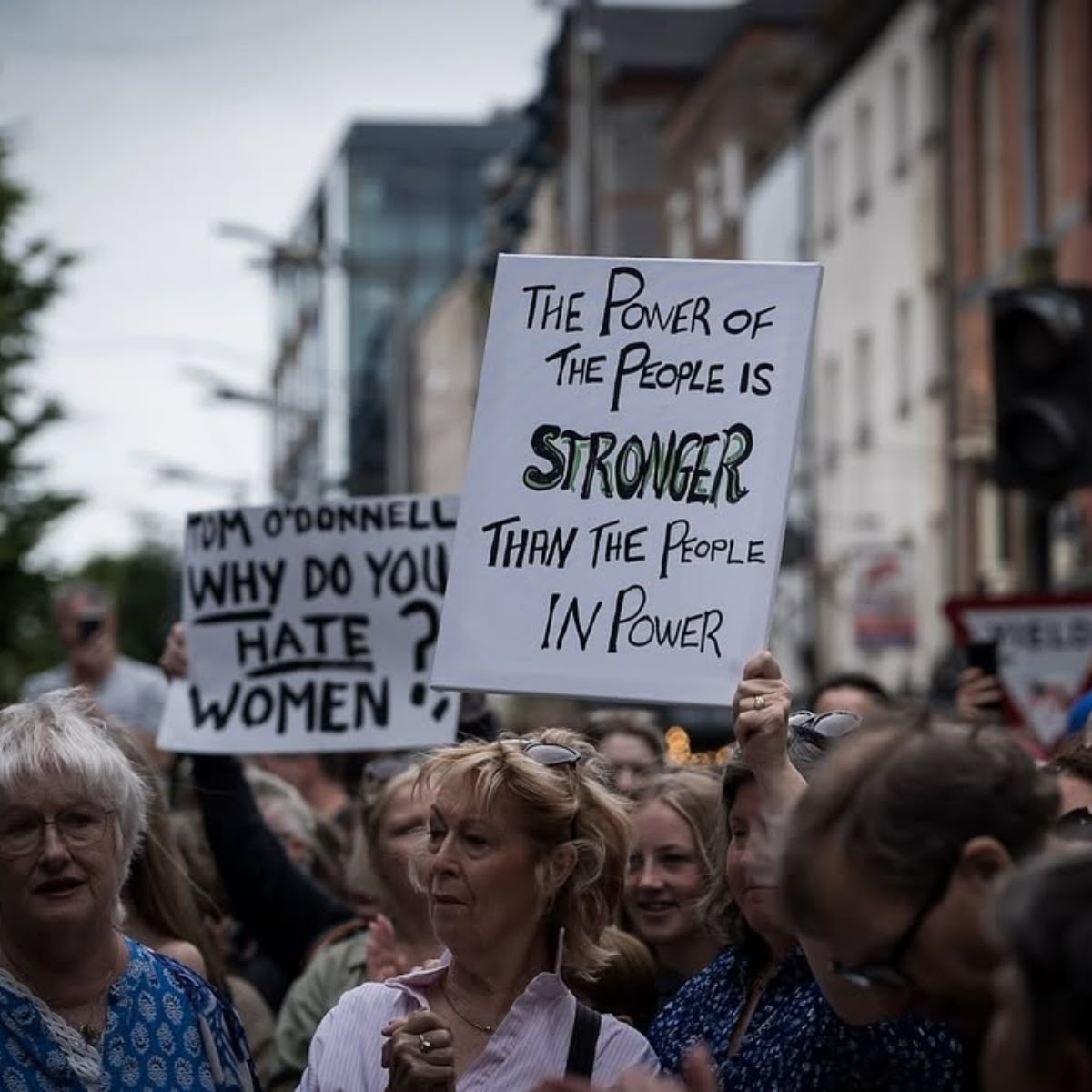

In July, Judge Tom O’Donnell imposed a three-year suspended sentence for assault causing harm, expressing concern that a prison sentence would certainly end Crotty’s army career. Less than a month later, he was formally dismissed from the Defence Forces. Appearing in court in his soldier’s uniform, his employment took precedence over Natasha’s trauma. As a result of the attack, she suffers from PTSD and depression, was deemed ‘high-risk’ for a brain bleed and lived in fear while he walked free.

I want the silent victims to get the same justice that I did.

The Director of Public Prosecutions lodged an appeal against the sentence on the grounds of undue leniency, and on Thursday, January 23, justice was finally served. Cathal Crotty was jailed for a two-year term, with the DPP arguing that the fully suspended sentence was unduly lenient, that it sent the wrong message and would not deter others from committing similar crimes.

“I have dedicated all my time and energy to campaigning and advocating and trying to get justice,” Natasha tells me in the aftermath of the resentencing. “We need to have the modern justice system that we deserve. We have such a wonderful society and it’s so frustrating that we have a justice system that does not reflect the good people of this country.”

The Court of Appeal hearing and decision, for Natasha, was a validating one. For the first time in an Irish courtroom, she felt in focus. “The judges really heard my victim impact statement, and they took it all into account. It felt like a milestone, but I want to see that implemented across every Irish court, whether a victim opens their mouth or not.”

What Natasha wants more than anything is for this milestone to serve as a stepping stone towards a justice system that will condemn violence and set a precedent that shows that acts of violence have consequences, that they will not be tolerated.

“It’s been frustrating to live in this country and see such widespread tolerance and acceptance. I want every one of us to feel safe at home, when we’re walking down the street, and to know that if we’re ever put in harm’s way, there is a way out, there’ll be a genuine response, and they’ll be protected,” Natasha says. “I’ve had to go to great lengths to get the bare minimum. I’ve had to scream and shout and I want the silent victims to get the same justice that I did. I don’t believe that justice for one person is justice, it’s privilege.”

Since the violent murder of Ashling Murphy three years ago, there have been 28 more women murdered by men in Ireland. A new study from the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre found that 25% of the men surveyed questioned whether sex without consent is as widespread a problem as it’s made out. Over Christmas week, a record number of domestic violence incidents was reported to An Garda Síochána, with a total of 1,600 calls for help received. Ireland does not feel like a safe place for women.

Though incredibly grateful for the result, Natasha remains optimistic that it will flip the script in Irish courts going forward so that the suffering of the victim can be centred, rather than the job or hobby of the accused. “Last week, the judges said that a suspended sentence could in no way reform public deterrence to violence,” Natasha continues. “It did not give any weight to the gravity of the crime — it totally enabled it. The reason I started campaigning was because the sentence did not act as a preventative. The sentence enabled violence, and that terrified me.”