Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls trilogy has been chosen for Dublin One City One Book 2019

By IMAGE

06th Sep 2018

06th Sep 2018

In November 2015, as Edna O’Brien’s first novel in ten years prepared for release, Aingeala Flannery looked at how the author’s work and influence continued to resonate with Irish readers, and book lovers the world over. Now, as The Country Girls trilogy is chosen for Dublin One City One Book 2019, we throwback to an article that is still as relevant today, as it was three years ago.

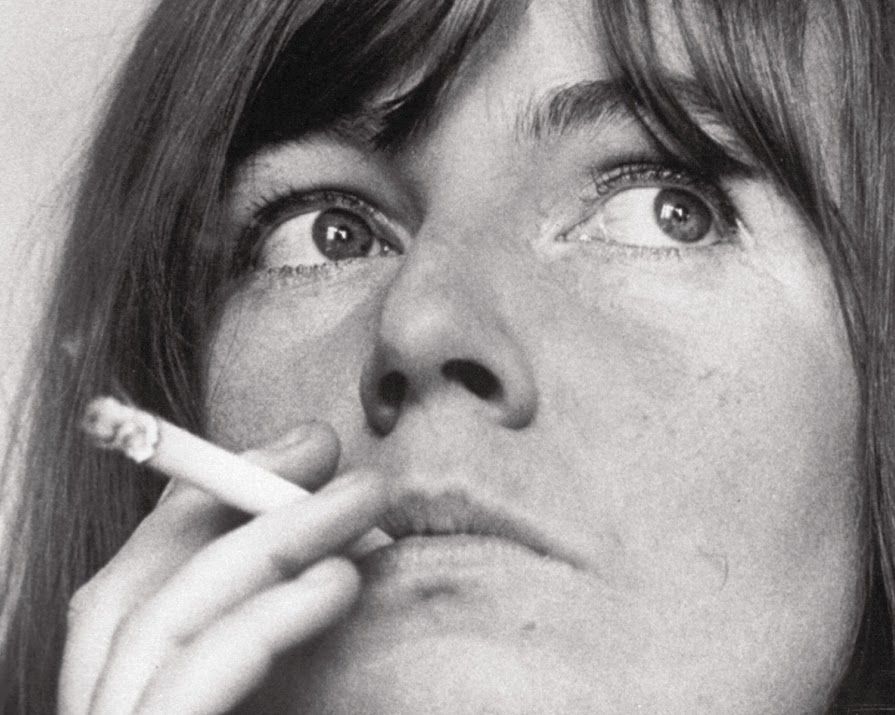

“Falling in love is glamorous hell” – it’s a line from a Carol Ann Duffy poem, but it always makes me think of Edna O’Brien. The words danced across my mind when I saw her on the RTÉ news, being made a Saoi, the highest honour bestowed upon an artist in Ireland. Now in her mid-80s, O’Brien still dazzles. She spits more glamour and damnation than a room full of women half her age.

I have never met Edna O’Brien, but I feel as though I encounter her all the time. During the summer, I was reminded of her when I interviewed Louise O’Neill about her novel Asking for It. The notion that only the virginal are blameless still runs in Ireland. The baton is O’Neill’s for now, but O’Brien carved it decades ago when she wrote The Country Girls, her first novel.

When it was published in 1960, the story of Baba and Kate coming of age was denounced from the pulpit, and every other cornerstone of morality and authority in Ireland. In O’Brien’s childhood village of Tuamgraney, Co Clare, the parish priest presided over a public book burning. The Censorship Board banned The Country Girls – and the two novels that followed it. O’Brien may have been a hit with the Bloomsbury set, but she was a pariah in her home country.

Yet, there were women who were privately in awe of O’Brien and wished they were so brazen. The teenage shop girl who had married the writer Ernest Gébler, eloped to London, had two sons with him, and when their marriage ended went on to eclipse him with her own writing – all the while keeping her dignity and her beauty intact. To a certain generation of Irish women, O’Brien wasn’t so much fallen as risen. She seemed to glide through a man’s world with grace and wit. And for this, she was also despised.

When I was a teenager, I found a copy of The Country Girls that had been passed between my mother and my aunts. I remember scanning the pages for filth, and being disappointed. Many years later, a writer I had fallen in love with gave me his coffee-stained edition. To please him, I read it immediately and was taken aback by how lyrical and raw and melancholy the writing was. She wrote it in a few weeks, he told me. He’d met her once in London and was smitten. O’Brien is a writer’s writer – “the most gifted woman now writing in English”, according to Philip Roth.

And so, over the years, I have kept tabs on Edna O’Brien. Yes, for her writing, but also curious at the discomfort her books seem to cause in Ireland. She continues to write from an Irish perspective – a habit that catches in the craw of the establishment and the so-called cultural elite here. She waves a mirror at them, and the grotesque reflection makes them wince. It began with provincialism and sexual morality, but as the church lost hold of the nation’s undergarments and Ireland spluttered into modernity, O’Brien cast a smoky grey eye over the authority of the State.

Her 1994 novel, House of Splendid Isolation, tells the story of the relationship between a Republican gunman on the run and the woman whose house he hides in. To research the novel, O’Brien visited the notorious INLA leader Dominic “Mad Dog” McGlinchey in?prison. That same year, she wrote a piece for The New York Times on Gerry Adams and described him as “thoughtful and reserved, a lithe, handsome man” who,?she said, could be imagined in a different incarnation as “one of those monks transcribing the gospels into Gaelic”.

Absurd as the analogy is, it signalled that O’Brien had moved beyond feather ruffling. She was hell bent on rubbing the nation’s nose in the mess of its own history. In the US, House of Splendid Isolation was praised for its “poignancy”. In Ireland, and in Britain, where any lionising of the IRA was intolerable – O’Brien was accused of stage Irishness and romanticising terrorism.

What was she up to? Was she playing with the notion that humanity and monstrosity are more closely related than we like to think? Nothing is straightforward in Edna O’Brien’s world. What is safe ultimately suffocates. Bad things happen to people who have done nothing to deserve it, but who are nonetheless difficult to feel sorry for.

She relentlessly prods at consensus and leaves a lipstick stain on the establishment’s cheek, not as a sign of affection, rather a token of contempt. She is, above all, a rebel.

And this is what we expect from writers. It’s what distinguishes them from the rest of us. We tolerate their impudence and awkwardness, but our patience is finite. O’Brien’s novel Down by the River, which was based on the X case, along with her support for the repeal of the 8th amendment, have not raised too many hackles, because they were not unexpected. However, her use of real life events for her 2002 novel, In the Forest, was met with such revulsion that even O’Brien herself seemed shocked.

The novel was a thinly veiled retelling of the murder of Imelda Riney, her three-year-old son Liam, and Father Joseph Walsh in Co Clare in 1994. The randomness and cruelty of the killing were so terrifying they seemed more grounded in fiction than reality. But they were real, and for O’Brien to use them as fodder for her novel was condemned in every quarter.

Writing in The Irish Times, Fintan O’Toole used journalistic ethics as a stick to beat her with. It was not in the public interest, he said, for her to have intruded into private grief. Then taking aim below the belt, he accused O’Brien of being motivated by money: “The imperative at work here appears to be far more to do with the selling than with the writing of a book.”? Whether it was that criticism that stung, or the many others that followed, O’Brien was still smarting nine years later when she told The Observer there are still certain no-go areas for women writers. Referring to Fintan O’Toole, she said, “Why would someone be so savage? I suppose it is that a certain kind of writing gets under the skin.”

I’m reading O’Brien’s new novel, and I have gotten to a passage that is so violent and disturbing, I had to put the book down. It’s called The Little Red Chairs, and it tells the story of a woman in the West of Ireland who falls in love with a Balkan war criminal. O’Brien’s writing is poetic and beguiling, but it is lethal. She does not inch, and I’m intrigued by that boldness.

Yet, there’s a meanness in the Irish psyche that compels us to bring high fliers down a peg or two. I wonder if Edna O’Brien felt some vindication when the President, in making her a Saoi, called her a “fearless teller of truth”? Did she appreciate that Michael D praised her for continuing to write, undaunted by “authoritarian hostility and sometimes downright malice”? I watched her face, and it was an inscrutable blend of shyness and devilment, with that ever-present melancholia in her eyes. Who knows what was going through her mind?

Like I say, I have never met Edna O’Brien. She says she prefers men’s company anyway – that women are always competing with each other. Would I like her if we met? Maybe I wouldn’t. It doesn’t matter. There are more important things than being liked.

@missflannery