By Lia Hynes

02nd Apr 2018

02nd Apr 2018

It was my birthday during the week, I turned thirty-nine.

Getting older doesn’t bother me; either way it’s happening so I don’t see the point in getting upset. And I always felt pretty happy with my lot, so the sight of forty approaching on the horizon didn’t scare me, there was nothing majorly missing that getting older would make me feel the lack of.

This year, obviously, was different. The first birthday since my husband and I separated. I was nervous the day would bring on some unwished-for reckoning, a sort of mid-life review.

The morning of I go for my run in the park and listen to a podcast of my friend Sophie White talking to Louise McSharry about grief; the surprising things it throws at you, the physicality of it.

Five stages is a deceptively tidy way to describe this most difficult of emotions.

My husband, in the aftermath of his mother’s death, once told me grief is more like waves. You never know when the next wave will hit, he said, and you can go from nothing to totally overwhelmed in a moment. Gradually, he said, the time between the waves increases, until you realise it has been awhile since you have felt that raw.

When you separate, there’s the grief for the life you thought you would have. The grief for the people you and your husband were on the day you got married. The grief for your child, the most difficult.

It’s a perfect description of an emotion which is nothing like the tidy progression of checking off stages, the end always clearly in sight, that the idea of five suggests.

Anything can set it off. A memory out of nowhere. A Garth Brooks song on the car radio, embarrassingly. Or just nothing, it arrives of its own accord.

Grief can make you distrustful of the good days, but at the same time make you grab them tightly and live in the now more than any self-help book would, because you know the grief will be back, and you’re not sure how long this feeling of buoyancy, of well-being, will last.

In my experience, it was as if something within knew just how much I could take. There would be days when it felt relentless, and then suddenly, gone, I would feel fine, better than fine.

Grief is unavoidable. Bury or try to ignore it at your peril. In describing anger, my counsellor once told me that you have to experience it, to sit with it. Ignore it and it will still be there, burrowing away somewhere. She described it as a crescendo, peaking but inevitably dissipating. In the feeling it, you are processing it, even though at the time it might feel scary. Grief is the same. It needs to be faced, acknowledged.

I go out for cocktails the night before my birthday and the next day I realise that sluggishness I feel isn’t low-lying grief, it’s a hangover. The two are not dissimilar. I realise I haven’t had one of those grief days in I can’t remember how long.

Days when summoning up the energy for anything beyond meeting a deadline and minding my child were beyond me? Gone.

Raw moments of feeling close to tears out of nowhere when out and about? Gone.

The feeling of exhaustion when I stepped outside my comfort zone (home, parents’ home, “gym office” with the Work Wife) for bigger jobs? Gone.

The feeling of relief on getting to the weekend, exhausted, glad another week was done and there would be two days of respite from keeping it all in the air? Gone.

The after waves of shock that this had happened to us, that came out of nowhere? Gone.

The all-over body tension that would manifest when I twisted a certain way and felt my back go? Gone.

During the week I interview psychotherapist Lisa O Hara for a piece, and in reading her book come across a paragraph in which she describes how one day you will realise the worst of the hurt has passed. Without thinking much about it, I’ve been trotting out something like this phrase to anyone who asks. “We’re past the worst of it”, I say. It’s an easy one to move the conversation along. It also happens to be true, I realise. Not a soundbite. I see myself in her words.

I can spot a woman who is going through this sort of thing, some major traumatic life event, without knowing her circumstances. Shook, I call it. To the core, should be the subheading. A person whose life has fallen apart and who is holding it all together when underneath they are broken, for now.

I recently met a woman whose husband is seriously ill. She had a beautifully warm smile but I could see the effort going into it. She is practically vibrating with the exertion involved in holding herself together. I could see it in my friend when her father died last year. I can see it in a woman I know vaguely who has recently separated.

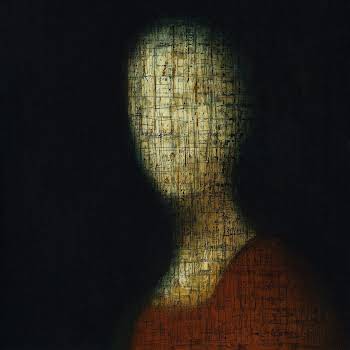

A strained smiling version of oneself pasted over the fractured version underneath, so there’s an almost blurriness to ones edges, as the two versions don’t quite meet as one.

At its worst, grief feels like it will never, can never, be better. But that is not true. You will feel differently about things. Even the things you thought might slightly break your heart for the rest of your life. A new normal will arise.