By Erin Lindsay

26th Nov 2019

26th Nov 2019

A viral Twitter thread made the case for why boundaries in relationships are essential — but is treating friendships as transactional really a healthy way to live?

“Hey, I need to vent”.

What emotion does the above sentence fill you with? Dread? Exhaustion? Cautious interest?

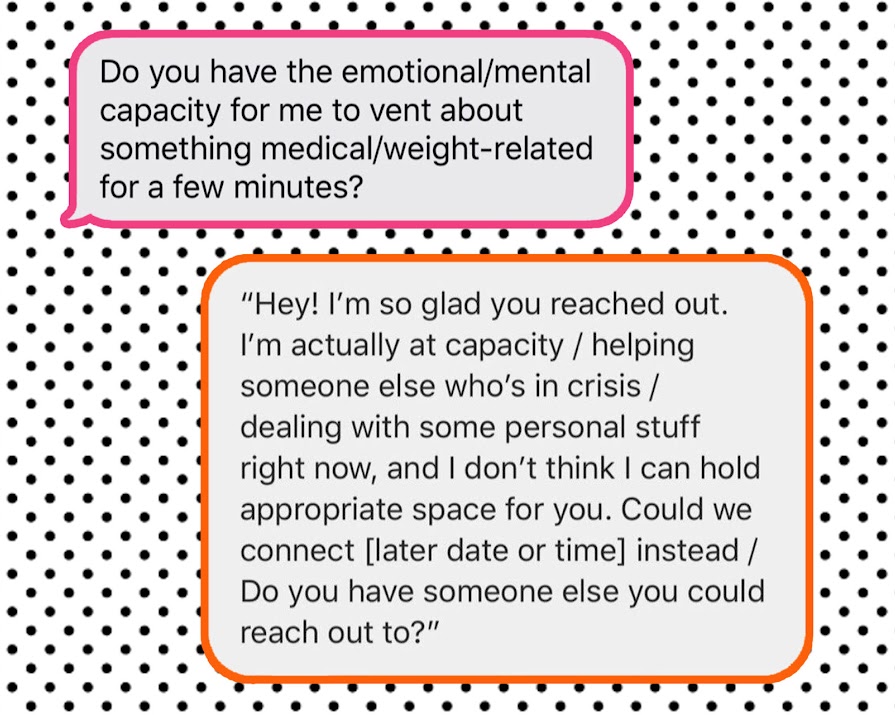

The simple act of venting between friends became the subject of fraught Twitter discourse last week, when a thread by user Melissa A.Fabello went viral. Fabello, who has a PhD in Human Sexuality Studies according to her bio, began a conversation on the dynamics of modern friendship when she posted a text she had received from a close friend that day, asking if she had the “emotional/mental capacity” to listen to her vent about a problem.

I want to chat briefly about this text that I received from a friend last week: pic.twitter.com/cfwYx3tJQB

— Melissa A. Fabello, PhD (@fyeahmfabello) November 18, 2019

Fabello went on to praise her friend (who she kept anonymous) for “acknowledging [Fabello’s] limited time and emotional availability” and “setting the tone of the conversation, so that [Fabello] wouldn’t feel barraged”.

“Asking for consent for emotional labour, even from people with whom you have a long-standing relationship that is welcoming to crisis-averting, should be common practice,” one of the tweets read.

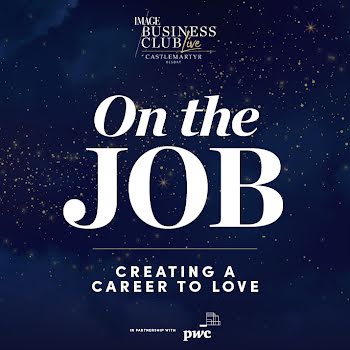

Fabello went on to share a ‘template’ on how one could respond to a friend who reached out for help when one doesn’t have the “space to support them”.

PS: Someone reached out and asked for an example of how you can respond to someone if you don’t have the space to support them.

I offered this template: pic.twitter.com/lCzDl60Igy

— Melissa A. Fabello, PhD (@fyeahmfabello) November 19, 2019

Empathy and connection

I had a lot of feelings about Fabello’s thread and her opinions on how friendships should operate. The presiding one was incredulity, followed by simmering rage, with a sprinkling of mourning for this generation’s apparent complete lack of empathy.

It seems to be an increasingly strong attitude in today’s young people that views time as transactional — if I’m not getting paid, I’m out. While this can be beneficial when it comes to jobs and the gig economy (i.e the only instance in which our time is actually transactional) and gives us the opportunity to learn from and bypass the millennial need to overstretch themselves for work, when it comes to friendships, it’s dangerous territory.

When we enter into a relationship only searching for what we can receive in return for our time, it’s not conducive to any type of actual connection. Friendships and romance become business partnerships — you scratch my back with so-called ’emotional labour’, I’ll scratch yours. Today’s social media-driven generation, who search online for their validation rather than in offline human connections, seem more concerned with how others can benefit them — whether that’s with money, status or likes and follows for online ‘clout’ — rather than how they may add to someone else’s life.

What does emotional labour actually mean?

The most starkly depressing term that Fabello repeatedly used in her thread was that of ’emotional labour’. Let that settle for a moment — emotional connections as ‘labour’. Hard work. Something to be paid for. Something to perform, rather than to feel.

Apart from the fact that viewing emotional connections as ‘labour’ is worryingly apathetic, it’s also just plain incorrect. The term ’emotional labour’ was first coined by sociologist Arlie Hochschild in 1983, and refers specifically to “displaying certain emotions to meet the requirements of a job”. Emotional labour is performative, and to be used in a job where a certain level of emotional interaction with the public/clients is expected by employers — think waitresses, or service workers.

It is not, as Fabello says, a way to approach your nearest and dearest when they have a problem. It is not an excuse to say you are ‘at capacity’ when a friend reaches out for help. It is not any way to maintain a friendship.

Mental health and being a friend

I came across Fabello’s thread in the middle of a particularly tough week. Myself and many of my friends were dealing with the death of a loved one, and were, collectively, in a pretty low place. So when I came across an exchange talking about boundaries rather than love, labour rather than support, and the importance of respecting “limited emotional availability” rather than the importance of support, it didn’t exactly sit well with me.

When we talk about mental health, we so often preach the importance of taking the first step, of reaching out to a friend and talking about your problems. Can you imagine building the strength to do so, and being met with an automated response effectively telling you that a friend will be provided in 5-10 business days?

When I thought about what would happen if I had have responded in kind to Fabello’s template to one of my friends who reached out to me during that dark week, I felt sick. I imagined how a cold and robotic response like that could affect a friend — I imagined how I, at any one of my lowest points, would have felt if my best friend had said that to me when I needed them.

Of course, I felt at my emotional edge last week — taking any more on felt tough. But listening to a friend vent is not an activity to gain payment or recognition for. It is not something you can add to the list and pick up on Monday morning. Being a friend is just what you do — you stay and you listen.

Let me keep the mess

As communication moves increasingly online, and conversations are increasingly edited and curated, it becomes easier to view any interaction as one just with a screen, rather than with the person on the other side. As much as we may like to appear cool in our responses, to screen our messages and pick and choose which are worth our time, there is no substitute for real vulnerability. Messy, awkward, draining, intense — that’s what friendship is.

Read more: The secret to keeping a secret (and why most of us can’t)

Read more: Internalised sexism: how to spot it and how to undo it

Read more: Sapiosexuality: Peak pretentious or legitimate sexual preference?