By Lia Hynes

31st Aug 2018

31st Aug 2018

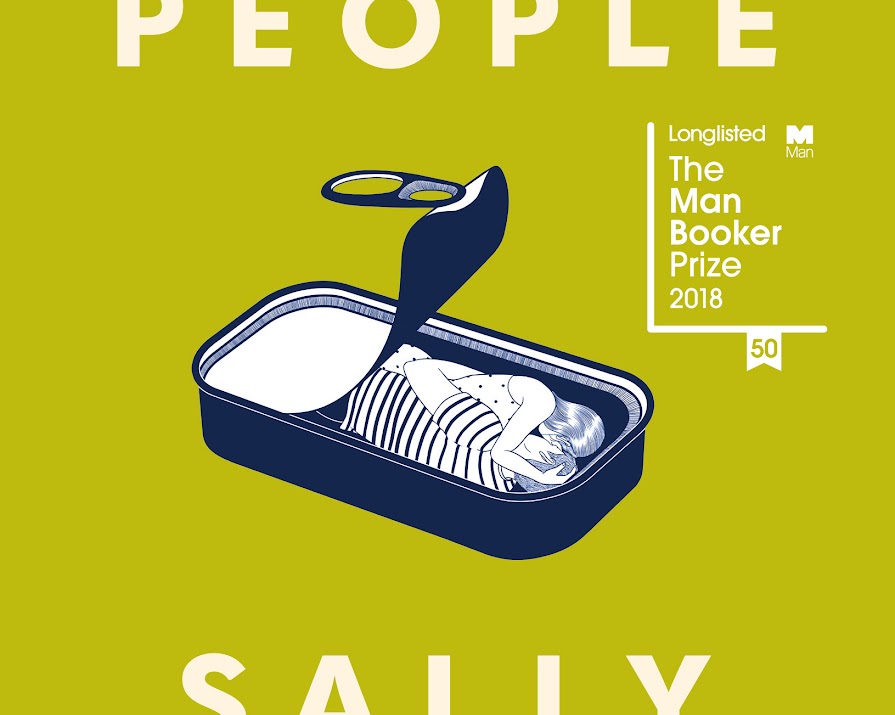

Sally Rooney’s much anticipated second novel Normal People published this week is a beautiful coming-of-age love story which will draw you in instantly. Set mostly in Trinity College it is the perfect back-to-school September weekend read.

Full disclosure; so engrossing did I find Sally Rooney’s new novel, Normal People, that I stayed up until three in the morning to finish it in one sitting.

This is Rooney’s second novel. Published this week, it has been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Lenny Abrahamson is making an adaptation for the BBC.

Normal People tells the story of Marianne and Connell, star-crossed lovers, of a sort, who grow up together in a rather unprepossessing town in the west of Ireland (chief highlights include the ghost estate and local Centra) before both attending Trinity.

Outward appearances would suggest the pair have nothing in common. Marianne lives in the big house with her cold, distant mother and threatening brother. Looked upon askance by her peers, at school she is an outcast, “considered an object of disgust.”

In part, it is that she is unrelentingly herself; an unforgivable sin in the conformist world of teenagers. Uninterested in the attention of her male classmates, a wearer of thick-soled flat shoes and no make-up, rumour has it she does not shave her legs.

She is in some way other; living in “the white mansion with the driveway”. This dichotomy between Marianne’s family’s economic status and that of her peers is the first reference to class status, a topic which Rooney forensically examines later in the novel.

Connell, though shy, is at the centre of the popular crowd; good looking, the football team’s centre-forward. He is also, secretly, an avid reader, both Marianne and Connell are hugely bright.

Where Marianne’s father, now dead, was a solicitor, Connell’s has never been revealed by his mother Lorraine (a warm, sensible, enjoyable side character), with whom he lives in a small terraced house. She works as a cleaner for Marianne’s family, and while in school they “affect not to know each other”, in fact, Connell and Marianne strike up an acquaintance when he comes to pick his mother up.

Soon, awkward teenage encounters blossom into a bond which Connell knows means “when he talks to Marianne he has a sense of total privacy between them.”

Unlike Marianne, who is never anything but herself, whatever the accompanying social ostracism, Connell is troubled by insecurity and social angst which preclude him from acknowledging the affair to their classmates. Things come to a head and the relationship, such as it is, sunders.

The pair are reunited in Trinity, where the tables have turned. Marianne is now at the centre of a rich, popular crowd, while Connell is struggling to fit in, college has merely served to highlight his inner identity crisis. Torn between being the working class, country boy intimidated by his rich, private school educated peers, and the highly intelligent sensitive creature he has only revealed to Marianne, he is an outsider at college.

On speaking about gender, Rooney once pointed out that “men have gender, which they never get asked about.” Here, she brilliantly examines the contradictions of masculinity. Where Marianne risks at times becoming something of an archetype, in Connell, and the bouts of depression he suffers, his fear around revealing his authentic self, his hidden inner softness, Rooney has created a brilliant depiction of what it is to be male.

As with her first novel, Conversations With Friends, which was published last year, Trinity College, Rooney’s own alma mater, provides a backdrop here.

Much has been made of Rooney’s ability to depict the world of post Celtic Tiger Dublin (she herself started college in 2009, after moving from Castlebar, Co.Mayo, where she grew up), but in fact this book finds much in common with classic novels which examine class structure, and the inviolable world of the upper classes, with Connell as the tortured interloper of lowly social status, and Marianne as the wealthy but broken beauty.

The college scenes; Marianne’s privileged set, her unthinking, careless acceptance of the luxuries of her world- her own apartment, allowance, holiday homes – have much in common with the world of Evelyn Waugh’s Oxford, as depicted in Brideshead Revisited, or the circle of Daisy Buchanan, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Luckily for him, Connell is not enticed by the glamour of this world in the manner of Jay Gatsby or Charles Ryder.

Rooney has spoken in interviews about how arriving at Trinity brought an awareness, for the first time, of class politics, that she found the world there both “glamorous” and “politically repulsive.” It is a tension which she portrays brilliantly in this new novel. The entitled vulgarians of Marianne’s set, offspring of the bankers who have brought about their country’s economic downfall, ostensibly accept Connell but never really consider him an equal.

“I’m only interested in writing about relationships, the dynamics between characters,” Rooney told the Irish Times in her recent interview. The small world she creates is the perfect setting in which to play out the intensities of the early twenties; the overwhelming relationships, the sense of one’s entire life being dependent on the choices they made.

In the book, neither Marianne nor Connell have much in the way of self- esteem. Both hold themselves in dismally low regard; Connell, because of his difficulty in reconciling himself to his true nature, Marianne for more sinister reasons which become clear later in the novel. Where Marianne turns to self-harming, submissive behaviour, Connell attempts to forge a new identity for himself, with a rather boring, conventional girlfriend.

Ultimately, these attempts fail, but that is not to say that this is a novel without hope. Far from it.

Normal People, Sally Rooney, Faber & Faber, RRP €14.99