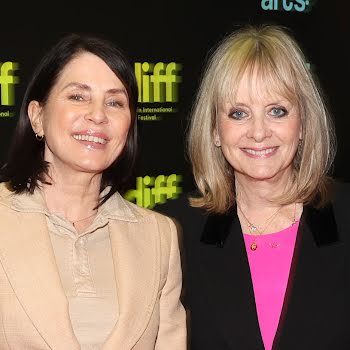

“Building is fun”: Architect Valerie Mulvin on her illustrious career

One of our most acclaimed architects, Valerie Mulvin’s career has been varied and impressive in equal turns, demonstrating the sheer breadth of her skills and interests.

In McCullough Mulvin’s studios, above the Molesworth Gallery in Dublin, the atmosphere is calm, yet intensely busy. People are working in a profusion of creativity, with models, drawings, notes and books everywhere. Some are of buildings already well known, such as Kilkenny’s Butler Gallery, and Trinity College’s Ussher Library; while others, including Bantry’s West Cork Music Centre, and the new headquarters for Poetry Ireland and the Irish Heritage Trust on Parnell Square, are yet to come.

It was from here that Valerie Mulvin and Niall McCullough designed their recent multi-award-winning buildings for Thapar University in India’s Punjab, bringing an additional million square feet of space to students, with environments to suit both searing summer heat and cooler winter times. There, on a table, is a model of my own house, a much smaller space, about to make the leap from an architect’s imagination to bricks and mortar reality.

Valerie co-founded the practice with her husband Niall in 1986. Since then, their thoughtful and inspiring projects and publications have shaped spaces for living, learning, working and playing. Niall died tragically after a short illness in 2021 and, headed by Valerie, the practice continues, making beautifully remarkable buildings in Ireland and around the world. Their architecture make you feel differently, in a good way. It’s things such as the way the light falls, in a just-so sort of fashion, the curve of an arch, or the exact height of a wall.

In our towns and cities, good architecture defines the streets and squares. In our homes, it defines our lives, and it is something Valerie and her team are adept at doing well. “Building is fun,” she says, in a cool and confident tone that makes you feel no detail or hiccup will prove impossible. “And it’s exciting,” she adds, clearly meaning it. In conversation she is one of those people who is fiercely intelligent. You get the impression that she wouldn’t give fools a great deal of glad time, but she is also really good company, with a strong streak of humour, and a great sense of adventure.

When a wider team of Ireland’s brightest and most brilliant young architects got together in the late 1980s to pitch for the redesign of Temple Bar, McCullough Mulvin’s contribution to the groundbreaking scheme was the Temple Bar Gallery and Studios. Despite the ebbing fame of “starchitects”, architects do work in teams, and buildings are the result of a combination of talents. “We worked back and forth,” Valerie confirms of her projects with Niall; and the work continues, such as with new healthcare buildings for older people at the Grangegorman campus in Dublin, which have just gone for planning.

Still, it would be a mistake to think that with such grand civic projects, Valerie has left domestic architecture behind. Making homes for people is a passion. “It is the most exciting and fun thing you can do,” she affirms. “You have a blank canvas, a piece of land, maybe a wall or a tree, and all of those things can spark off an idea that suddenly begins to make real sense to you.”

“You see it all coming together,” she continues. “When the elements of the building close in, when you have a roof, and windows, and you suddenly have a set of spaces with views out, and new relationships.

It’s a beautiful thing.” Does she ever get dismayed when people put horrible curtains or hideous sofas into her lovely buildings? She laughs. “I think we’ve been really lucky with the clients that we’ve had.” It’s obviously reciprocated, as many have become friends.

“I think I was about 13 or 14 when I knew what I wanted to do,” Valerie remembers. “I mean, I didn’t really know what an architect was, but I had an idea that there were people who made spaces that people lived in. I don’t know where the idea came from, but I was always drawing things that excited me, that I had seen in magazines. Ours was not a ‘magazine house,’” she notes, recalling a childhood friend whose arty parents and home were a world away from the identikit houses she had been familiar with while the family were living in England. She also collected stamps, and recalls the thrill of seeing such faraway and extraordinary buildings as Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame du Haut church at Ronchamp in France. “I thought, wow – you can make buildings like that?”