How can we expect small businesses to operate in an economy of ever-rising costs?

The tsunami of restaurant closures has left hundreds of Irish chefs, restaurateurs, waitstaff and customers feeling extremely disheartened at the current state of the industry, and the retention of the 13.5% VAT rate in Budget 2025 has brought tensions to a head. Alex O’Neill lays it out and calls for immediate action.

Restaurants have always operated on tight margins, and the hospitality industry has long been known for its instability, challenges, and difficulty as a way to make a living. But in 2024, the business is rapidly shifting from “tough” to “unsustainable”.

Known for its resilience, hard work, and fearless risk-taking, the hospitality industry has weathered a pandemic, soaring inflation, and a dysfunctional job market, but is once again being forced to redefine its offerings, identify gaps, and find solutions to external challenges. However, we’ve now reached a point where the industry seems to have nowhere left to go, and so this tsunami of closures has taken hold.

The Restaurants Association of Ireland (RAI) recently shared that an “average of two restaurants, cafés and other food-led businesses close each day across the country”. Even though we are all aware the industry is in trying times, the figures are shocking when you consider the real people behind each closure. Businesses that have stood strong for decades, weathering economic storms like the global financial crash are now folding under the pressure, while newer establishments that defied the odds during COVID and survived in uncertain times are struggling to find their place in a post-pandemic world. The game has changed, and for many, the challenges have become too steep to overcome.

There was a lot of hope that Budget 2025 would provide some reprieve, but instead many in the industry are saying it has brought more difficulties and more costs, along with what seems like very little support. Many are arguing that the Government has outright ignored the pleas of an entire industry, which led to members of the hospitality industry marching on the Dáil on Tuesday, October 15. There is huge frustration, considering Finance Minister Jack Chambers failed to even acknowledge the hospitality industry in his Budget announcements a couple of weeks ago, and the industry is asking, rightly, what next?

Creative solutions and seemingly endless pivots

The industry is not new to needing to find new solutions and pivots. We have seen immense creativity over the last few years, as people deal with difficulties with remarkable ingenuity; cafés have opened up wine bars, their own shops, or flipped them after close to reopen as casual evening spots with small plates. Restaurants have invited in pop-ups, private hires and brand collaborations. Food trucks have offered masterclasses, retail products, and merchandise. Coffee shops have opened up shop fronts, pop-up bakeries, even barbers and tattoo studios.

We have seen collaborations on rents, with businesses joining forces in order to meet the day-to-day costs of opening, with residencies and partnerships. Food retail business has never been more creative, more visible, and is even making waves abroad. All have invested in social media managers and PR companies, and have seemingly said yes to every Instagram reel interview request that comes into their DMs. Everywhere, across the country, people are trying to find revenue in any place they can, but it’s just not enough for so many places.

So, what has caused this? We know that a total of 612 restaurants, cafés, gastropubs and other food-related hospitality businesses have permanently closed their doors since the VAT rate for the sector increased from 9% to 13.5% on 1 September 2023, but is it as simple as that?

Rising costs and a post-pandemic world

According to the RAI, it’s due to a collection of difficulties; “Wages, inflation, a VAT increase, warehouse tax and rising supplier costs are crippling our sector.” The most obvious culprit behind these closures is the rise in costs. Ingredients have trebled, energy costs have quadrupled, staff and operating costs are all up across the board. Large suppliers are increasing prices multiple times a year, often with little notice, and rarely with explanation. Adding to this, the climate crisis is impacting crop yields across the supply chain, causing record-breaking price increases on things like chocolate, coffee, olive oil and more, but if this is across the board, why are SMEs being most affected?

Inflation has hit hard, particularly for small businesses. Large corporations with more pricing power and economies of scale have been able to manage these price rises without losing customers. Smaller businesses don’t have that luxury and this imbalance in pricing power has severely squeezed their already thin profit margins, challenging restaurants’ ability to maintain any profitability.

These cost increases can’t all be foisted on consumers, as prices have already come close to the top end of what people are willing to pay. As Bord Bia points out in a report from last November, “Consumers are cutting out spontaneous dining, in favour of other activities and choosing to eat out for special occasions.”

Meanwhile, profits of the largest energy companies, supermarkets and insurance companies operating in Ireland have also been well reported on, with many increasing their year-on-year profits in 2023 and projected to do the same again this year. Something has got to give, and typically, small businesses are the ones to give first and will continue to buckle under this.

A big frustration being felt right now is that the Government have not only not done enough to stop this profiteering *cough* I mean inflation, but they are also adding more pressure onto small businesses.

In 2023, VAT went from 9% to 13.5%, a huge jump of almost 50% for an industry where profit margins are often between 4–8%. A recent report by accounting firm Outmin found the average profit margin for food-led hospitality businesses in Q1 2024 was just 0.8%. In Q4 2023, the average net loss was 1.6%.

Adding to this pressure are more incoming costs related to staff supports, which aim to deal with the cost of living crisis for workers. The increase in minimum wage, the automatic enrolment pension scheme, sick leave pay and associated staff-related costs are all coming, all at once, and soon. These are all much-welcomed supports for workers, but are also putting further costs on SMEs who are already squeezed — it’s bound to force some to bow out.

Not to mention the debt warehousing scheme for the Covid supports the Government gave businesses to keep the economy from collapsing during lockdown, the bangs on the door from Revenue officers with threatening letters and red stamped demand notices. People are under severe, prolonged stress, and not coming from a place where they can easily think and come up with a rectifying plan of action. There are a lot of bills coming in at a time when hospitality is simply not able to pay up.

Food journalist Shamim de Brún highlighted that although it’s the smaller, local producers that are less able to bear these costs, it’s actually a double loss as these businesses often contribute more financially into the economy. “My biggest fear about these closures is the impact in the long term. I’m afraid that rents will get so high that people can’t afford them, and that nobody here will be able to set up their own business, only the large international conglomerates… [local businesses] actually contribute more into the economy overall, rather than profits being filtered out of the country.”

Shamim also spoke of opportunity and potential supports which could transform the industry, such as a ‘Support Irish’ grant, which could provide relief for businesses to use Irish products, or perhaps an expansion of grants similar to those currently available through the Arts Council.

“There is a real monetary incentive for the Government to support the industry and Irish owned business as the spend and profit from them comes back into the economy. We aren’t seeing that support, incentives or reliefs, which needs to be considered.”

Most people agree that it is pretty unrealistic for the Government to expect small businesses to operate in this economy of ever-rising costs, and at the same time be able to provide the same level of staff support as multinational giants can, without making any adjustments to their tax liabilities. After all, it’s not like the Government hasn’t bent over backwards to give big global corporations operating here a break—granting effective tax rates of 0–2.5% on profits funnelled through Ireland’s tax treaties that mean a real tax rate of 2–4% for foreign multinationals, while small businesses are stuck paying full freight as if they missed the “buy-one-tax-haven-get-one-free” deal.

But hey, the Government denies we’re running a mini tax haven, so I guess we’ll just have to take their word for it. This is the same Government that swore Apple didn’t owe us €13 billion—until the EU’s highest court said that actually, they did. Sure, maybe it sounds like Ireland has its own tax club where the entry fee is too steep for locals, but the foreign multinationals and vulture funds get the VIP pass.

Like the saying goes ladies, if he wanted to, he would!

Impacts on owners and staff

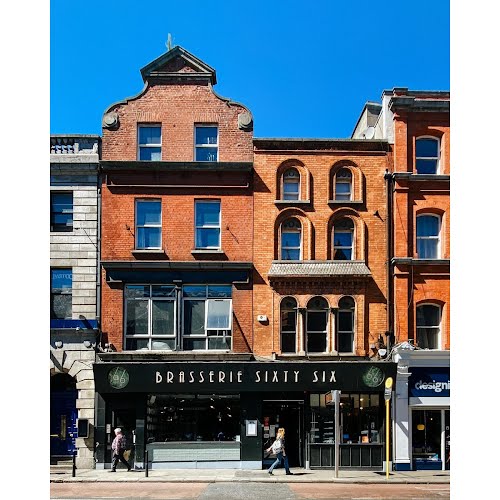

There are lots of figures here, but I think it’s important to recognise the human costs behind these closures and the extreme financial and emotional stress. Business owners often invest their life savings, and when forced to close, they not only lose their livelihood but also experience significant personal loss. I spoke to Vanessa Murphy and Anna Cabrera who run La Gordita and Las Tapas de Lola in Dublin 2 about how the news of these closures affects those still running their own business.

“It’s heartbreaking. Every day when we open up our phones we read of a new closure. The majority of these closures are independently owned, family-run businesses who tried their best but just couldn’t take it any further. We are all on a knife edge right now, every single SME in this country, not just hospitality.” Vanessa says.

On the worry of the next round of cost increases, she continues, “I don’t know anybody in this industry who’s against the important pro-worker initiatives. We agree with [them]. But there is a knock-on effect. We have to find an additional €65,000 a year to pay for these initiatives. We had to find an extra €65,000 for increased VAT in the last year. There are hidden costs behind these things, additional work and admin. These important initiatives have to be staggered, and brought in a way that [SMEs] can manage them.”

The pressure of sustaining, and indeed working in a failing business can lead to anxiety, depression, and even burnout and we are seeing this very real impact on the people who have brought Ireland’s food scene forward to a place where we have international recognition. Skilled chefs, entrepreneurs, restaurateurs, and staff are leaving the sector altogether, and many young chefs who would have once considered opening their own businesses are now choosing safer, more stable options.

The outlook

A survey conducted by Interpath Advisory and the RAI shows a concerning pessimism within the industry. Almost 70% of respondents said that trading conditions had deteriorated for them over the past 12 months, and 62.8% said their business had traded below expectations. This comes after a report by Outmin and the RAI exposed the precarious state of Irish food/hospitality businesses, with average net-profit margins at just 0.8% in early 2024.

Richie Castillo of Bahay said the current landscape has forced him to rethink everything about the business: “It’s a scary industry to depend on… Covid showed me how disposable I was working in hospitality.”

For Castillo, the reality of running a business in the post-pandemic world has meant constantly reassessing finances and finding new ways to stay afloat. The beacon of hope that once guided him through the tough times now feels distant, as rising costs and dwindling profits force him to make decisions based purely on financial necessity, not passion: “As a business owner, I feel like I have more to lose, the worries of being able to pay staff and suppliers is much greater than any personal worries I had before. I can’t just get another business in the same way I could just get another job. It seems like the things stopping us are outside our control.”

But the industry faced troubles like this before, surely we can get out of it?

The 2008 financial crash had a paradoxical effect on the global culinary scene. In Ireland, while many established businesses closed, a unique window of opportunity opened up for up-and-coming chefs to experiment with new concepts, spaces and business ideas in a financially accessible way.

Neighbourhoods transformed as small coffee shops, casual dining spots, and local restaurants brought life to previously empty streets. There was a growing emphasis on sourcing local, Irish ingredients, inspired by a global farm-to-table movement. The financial constraints of the time encouraged chefs to work with these local ingredients, develop relationships with micro suppliers, employ waste reduction measures, and even forage produce themselves, which fit into a larger global culinary revolution centered on environmental consciousness.

But in 2024, we’re seeing the opposite.

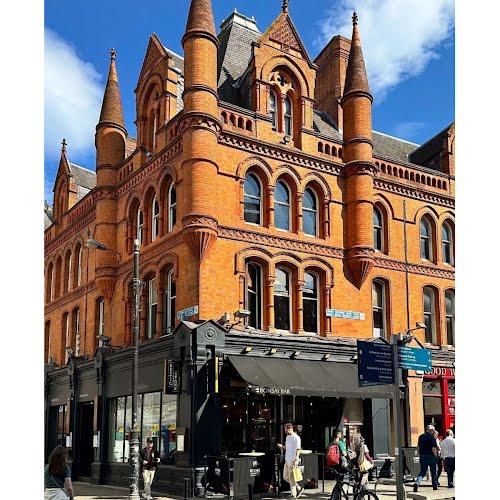

Despite the wave of closures, rents have not dropped, and property speculation has led to empty units being left vacant, rather than offered at lower rates. We’re seeing chains and faceless international corporations take over. Vibrant, community-focused spaces are being replaced with soulless, cookie-cutter businesses, and once-bustling neighbourhoods are losing their character.

We’ve seen spaces once inhabited by small, family-run operations be taken over by chains within weeks. News of Ukiyo, days after closing, being replaced with a “fusion” chain, an omen of what comes next. This isn’t new, the city has seen much of the same the last few years; old pubs being taken over by Wetherspoons, Centras, or simply knocked down to be replaced by empty, uninhabited office blocks.

The Tivoli, where generations went for school tour plays, nights out and music events, flattened for a passionless, soulless hotel that looks the same as the seven others which have taken over similar spaces all across Dublin 8. Once vibrant spaces are left to rot, small independents are shoved out as soon as developers decide that street is the next to be concreted over with an architecturally insulting block of student accommodation or a foreign investment-owned hotel chain. What will take up the space Dillinger’s held in Ranelagh for almost 15 years, who will step into the footsteps of Jackie Lennox’s famous Cork chipper?

The industry, known for its innovation and resilience, is now at risk of becoming stagnant as fewer and fewer small businesses can survive the financial pressures they face. To see all of this progress and innovation be smashed by a bottom line would be heartbreaking, and although too late for some, it’s not too late to support those who are left.

Hope in trying times, a call for action

We’ve seen the industry get itself out of holes before. Ireland is a nation that’s not afraid to pour money into things. I think it’s important to ask the Government why the pressure is on the industry to fix this when so many of the issues are outside their control. When will the Government decide it’s time to come in to support the industry and our food culture as a whole?

For decades, the Government has been more interested in attracting foreign investment than in nurturing homegrown, indigenous industries. When it comes to food, Ireland’s focus has always seemed to look outward rather than inward. It’s time the Government wakes up and realises the potential in nurturing these homegrown industries.

Though imperfect, there are sectors in Irish society that have been positively impacted by solution-driven supports, like the IDA and the Arts Council. Sectors like tech and pharma have long-term strategic funding, tax breaks, grants, training programs and international showcases — why are food and hospitality being left out?

The disappointments of Budget 2025 are not new. Ireland has historically focused on exporting its food, leaving its domestic food culture to fend for itself. Rural communities with incredible local produce have kept the torch burning, but they need government backing.

It’s time for real support—tailored grants, long-term programs, and Government investment in Irish food culture. If we can back our artists, musicians, and multinationals, why not do the same for Irish food and hospitality?

We could use proven strategies to boost Ireland’s food and hospitality sector, taking inspiration from successful European models like the D.O.P. (Denomination of Protected Origin) scheme, which protects and promotes local artisanal foods, boosting their value and preserving heritage. Ireland has barely tapped into this potential—only a few products like Waterford blaas or Imokilly Regato cheese have received this status, despite many others qualifying like Connemara lamb, our legendary Irish butter, our world-revered seafood.

A dedicated Hospitality Council, similar to the Arts Council, could focus entirely on supporting Ireland’s food and hospitality sector through grants, mentorship, and financial aid to drive innovation and growth. This support would include grants and bursaries for independent restaurants, cafés, and food producers, as well as opportunities for chefs to develop new Irish cuisine or projects centred around local ingredients.

Government-backed efforts like Fáilte Ireland campaigns could help revitalise the industry and create interest at home and abroad, rather than only targeted at international tourism. We can see how busy food markets are every week, and the growing grá of Irish society for small, independent producers is clear by the numbers who show up to get their pastries, organic veg and juices.

Training and upskilling programs for chefs and hospitality owners would provide essential culinary and business management skills to ensure long-term financial success. Finally, promoting Irish products and offering tax breaks to businesses that use and promote high-quality Irish ingredients would help preserve Irish food heritage, all while stimulating the domestic market. It all comes back to what a wise woman once said, if he wanted to, he would, ladies. And we need to remind the Government of this.

The effervescent willingness to find solutions, and an unwavering drive to make it work, in whatever way possible, has already fuelled Ireland’s hospitality many times over. We can’t allow this period of difficulty to drown this out or extinguish this energy from such a wonderful sector. Support local businesses, support the VAT9 campaign, and help the industry demand change from the Government in the form of real, tangible support.