Why the music of Sinéad O’Connor will stay with us forever

As every word of Sinéad O’Connor’s “Three Babies” comes flooding back, stylist Jan Brierton reflects on how Sinéad’s music lights up the pathways of her life, from school discos and fashion to familiar demons and long-term battles.

My menopausal brain is as foggy as ever these days. I forget all the important stuff: email passwords, alarm codes, school bake sale dates. Yet my brain, even in its mushiest of states, has the capacity to store very specific, usually useless, information. Like the ins and outs of a story line from Grange Hill (when Justine became addicted to catalogue shopping) and the music Ian Beale played at a dinner date with Cindy in Eastenders (“Your Love Is King” by Sade).

That day in work, I struggled to remember a photographer’s name, I walked into the kitchen and immediately forgot what I’d gone in there for, and I tried to pay for a coffee with my Leap card. But somewhere in that middle-aged brain I had stored all the words to the Sinéad O’Connor song “Three Babies” from 1990. I didn’t know they were there until the song played on the radio that evening, as I stood at the kitchen sink washing dishes. Every lyric, every beat, every melody of that song came flooding back.

It felt as though John Creedon was waking Sinéad O’Connor on his RTÉ Radio 1 show that night, just after the news of her passing had been announced. It felt like a musical vigil, there were no words, no anecdotes, no grand speeches, it was just her voice and her music. Her art. I moved around the house with my little Roberts radio playing Sinéad’s songs. Some so familiar and others I’d never heard before.

“Three Babies” was a song that I used to sing as a lullaby to the little girl and her baby brother that I babysat as a 15-year-old in Tallaght. Listening to that song, I remembered cradling the little boy and gently singing the words, feeling a warmness as he dozed off in my arms. I’d slip him into his cot and go downstairs to a living room in a house that always felt more modern than ours, with more TV stations than ours, with nicer snacks than ours. I’d watch The Word, or Vic Reeves Big Night Out – all the stuff I wasn’t allowed to watch at home.

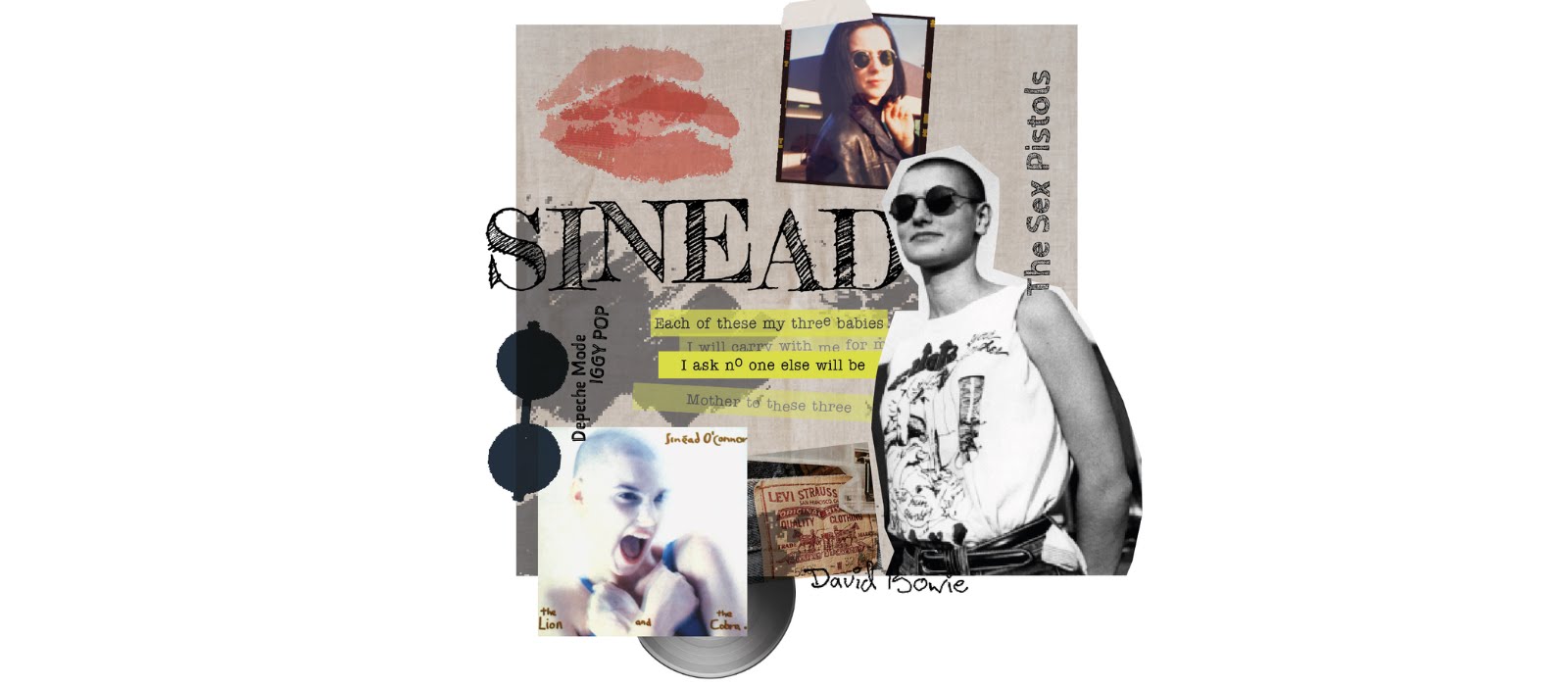

As a teenager, I lived and breathed music. My secondary school satchel was one of those canvas webbing ones from an army surplus shop. A small, A4-sized, rough yellow crossbody bag with a special shoulder patch. The strict confines of my convent school uniform meant there were very few ways to visually express who I was. And so, the school bag became my canvas. Sinéad O’Connor’s name was on that bag, written carefully in block capital letters with a permanent marker along with as many other names as I could fit. Every inch of it was covered. Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Depeche Mode, The Smiths, The Cure, The Wonder Stuff, The Sex Pistols (I always hoped Sister Theresa might ask me about them). It was a who’s who of mostly male indie artists. I think Sinéad, Blondie (Debbie Harry) and Curve (with singer Toni Halliday) were some of the only female artists on there. I was more of a music fan than a die-hard Sinéad fan, but she had earned a place on my bag and in my musical landscape.

Buying records was my favourite pastime and carrying that big record bag under your arm on the way home from the record shop was a signal that you knew about music. The local disco in the community centre in Kilnamanagh was “one size fits all” musically. At the weekly disco, myself and a few of the local indie kids would arrive with our albums or 12 inches under our arm. We’d present the visiting DJ (Tony’s chart-topping mobile disco!) with our selected records, giving him careful instructions to play a specific track and side. I had Sinéad’s album The Lion and the Cobra on vinyl.

Side A, track 2. “Mandinka”. Sinéad was getting played on the radio and the DJ would be more inclined to play the stuff he was even vaguely familiar with; he’d put the obscure stuff to one side. And so, we’d sit there and wait in our Dr Martens, crimped hair, and leather jackets. Those opening guitar lines were instantly recognisable and I and the other local misfits would leap from our chairs onto the clearing dancefloor. In the pink blinking disco lights, we’d punch the air, shake our heads, stamp our feet. And sing along. Even the rockers got up for “Mandinka”. None of us knew what a Mandinka was, but we mouthed with certainty that, just like Sinéad, we did. “Mandinka” was a song of connection and freedom for us. It gave us a sense of community on that dancefloor while all the others looked on.

Some of Sinéad’s songs are my snapshots in time. If “Mandinka” is community and connection, then “Nothing Compares 2 U” is smeared red lipstick on some fella’s face. “Nothing Compares 2 U” was a slow set standard. And in Mary’s, an indie weekly disco not far from where I lived, I’d just snogged some skinny boy with black spikey hair and a leather biker jacket for the full song (all five minutes of it). Now my Rimmel red lipstick from Tuthills was all over his gob and his chin. “Nothing Compares 2 U” is the smell of the dry ice and the sticky feeling of a sweaty cheek against yours as you both do the “walk around slowly” dance.

I remember the conversations in my house after the many appearances Sinéad made on The Late Late Show. My mam would always say how breathtakingly beautiful Sinéad was, “even with her shaved head”. My dad might say how “off the wall” Sinéad was, particularly after her appearance as a recently ordained priest. I never really enjoyed her interviews with Gay Byrne. It felt uncomfortable watching the audience of what seemed like elders to me, sitting cross-armed looking at her and smirking. I thought The Late Late was old people making fun of young people sometimes. Especially when they’d invite the latest youth “pop sensation” or craze. There’s no reason why someone brilliant shouldn’t be young, I thought. And that was Sinéad then, young, brilliant, and brave.

I credit my teenage obsession with music for my love of fashion. And I regularly look to my past musical favourites for inspiration. Over the years researching looks for shoots or styling projects, I’ve often fallen down a Sinéad O’Connor 1990s fashion rabbit hole. The Levi’s, the oversized T-shirts with sleeves hacked off, those round framed sunglasses, and the biker jackets. Of course, the “Nothing Compares 2 U” video was so visually rich. I loved the flow of Sinéad’s coat as she strides around the gardens.

One of my favourite pictures of Sinéad is from Q Magazine in 1994. The photographer John Stoddart talks about Sinéad shaking like a leaf at their session. There is a nervousness about this image of her. He says he thought Sinéad was all about “the lack of love, or the looking for love”. In the picture, Sinéad’s left hand is raised to her collarbone. She has the letters L O V E on each finger. The pictures ran in the magazine alongside a fax from Sinéad announcing a vow of media silence. “I no longer wish to tear myself apart,” she wrote. I never thought Sinéad tore herself apart. I always thought the media did that.

In the run-up to the summer of 2021, when her memoir Rememberings was published, I was so happy to see and hear Sinéad in the many promo interviews on TV and radio. One of my favourite interviews with her at this time is the episode she did with Róisín Ingle for The Irish Times’ The Women’s Podcast. Sinéad sounded comfortable and sure. Unapologetic. She spoke with candour and clarity about herself, her career, her art, and her own mental illness. It felt like this was her time. Finally, she was being heard, and celebrated. She spoke also about her surgical menopause after a radical hysterectomy. And her “mamma bear” protective love for her children. She sounded courageous, and she sounded hopeful.

It’s hard to feel like you’re falling apart. I know. The complexities of motherhood, the constantly shifting love. The instinct to protect, but the need to let go. The hormones. The world and its unkindness. The urge to create, to be doing something. The constant trying to make sense of yourself and the adaptive nature of the relationships you have with your children, your partner, and your loved ones. The loyalty and respect that you need but can’t always accept or even feel. Listening to Sinéad talk to Róisín, I felt I could relate to so much of her weakness, but there was huge strength there too.

I still play “Mandinka” in my “kitchen disco” while I wash dishes, sweep the floor, or get dinner ready. The lino is my dancefloor, the sweeping brush is my microphone, and the cooker is my instrument. And for those few moments I am there at the community disco, arms flailing, lost in the music and not caring what anybody else thinks. Feeling different but at the same time knowing that I belong.

And on that evening when all the words to “Three Babies” came back to me, I sang the song again, but this time it wasn’t a lullaby. The lines “No longer mad like a horse. I’m still wild but not lost, from the thing that I’ve chosen to be” made a different kind of sense. This time I sang as a middle-aged woman, and mother. Not always perfect, not always easy, a bit messy and misunderstood. Loud, full of love and impressed that my frazzled brain had stored these powerful words of Sinéad’s and kept them safe after all those years.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of IMAGE.

IMAGE Summer 2024

The Summer issue of IMAGE is here, and we’re taking the longer days as an opportunity to slow down, take stock, and luxuriate in the lull that summer brings. From laid-back looks to in-depth reads, there’s everything you need to set you up for the season. Plus: * Warm-weather style * Boho is back * In studio with Irish designer Sinéad O’Dwyer * Career success stories * Growing and foraging * Women in music * Reframing divorce * Tackle your tiredness * Summer beauty favourites * Bringing the outdoors in * Irish eco escapes * Garden getaways * and so much more…

Have you thought about becoming an IMAGE subscriber? Our Print & Digital subscribers receive all four issues of IMAGE Magazine and two issues of IMAGE Interiors directly to their door along with access to all premium content on IMAGE.ie and a gorgeous welcome gift worth €142 from Skingredients. Visit here to find out more about our IMAGE subscription packages.