IMAGE Book Club: Read an extract from ‘Web of Lies’ by Aoife Gallagher

By Sarah Gill

28th Nov 2022

28th Nov 2022

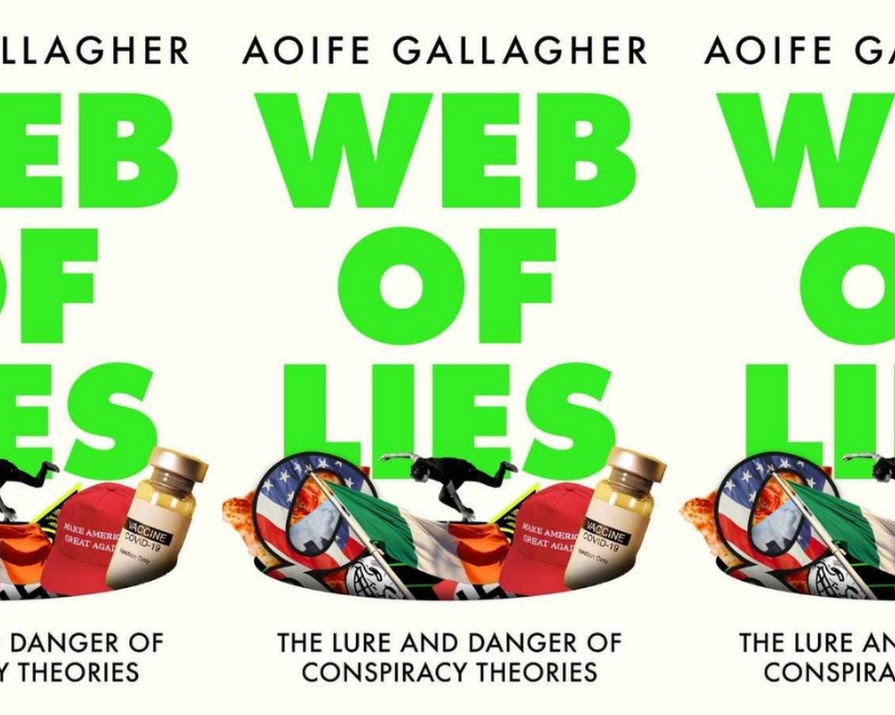

This week’s IMAGE Book Club title of choice is Web of Lies by Aoife Gallagher.

Through her newly released book, Web of Lies, Aoife Gallagher provides a fascinating and far-reaching examination of the rising threat of far-right extremist thought in Ireland and internationally, and looks at how these movements utilise the online world to spread disinformation, polarising society in the process.

From the Illuminati to the Red Scare, Save the Children to QAnon, research analyst Aoife Gallagher shows that there are many pathways to radicalisation – most of them benign and unassuming – and demonstrates that we are all susceptible to conspiratorial thinking and at risk of falling down the rabbit hole.

Read an extract below…

In 2008, when I was 19 years old, I was introduced to a film called Zeitgeist. It was an intriguing production, laced with hypnotic imagery, smooth narration and rhythmic music. The film was split into three parts. The first was about Christianity. It claimed Jesus was a fictional character and that the Christian faith was mainly based on a combination of ancient astronomy and parts of other religions. It was quite convincing, especially for someone who had stepped away from the Catholic Church. The second part was about September 11. This really interested me. Exactly 10 weeks before that fateful day, on 26 June 2001, I was standing on the observation deck of the South Tower of the World Trade Center gazing over the skyline of New York City while on a family holiday. I was 12 years old.

Like everyone who has a memory of the events of 9/11, I couldn’t look away as the news replayed the videos of the planes hitting the Twin Towers. The spot I had stood in only weeks earlier folded into a mushroom cloud of its own debris, and thousands of people ran for their lives as thousands more died. We had just been there. As a result, throughout my teenage years I was quite obsessed with watching anything and everything about 9/11, so when Zeitgeist presented me with an alternative theory about what happened that day, I was all ears. One of Zeitgeist’s main claims was that ignited jet fuel from the planes wasn’t hot enough to melt the building’s steel beams; it suggested instead that the Twin Towers had actually fallen in a controlled demolition. It questioned whether an aeroplane had even hit the Pentagon, suggesting rather that it was a missile, and it even raised doubts as to whether Flight 93 had really crashed in Pennsylvania.

These claims were all tied together by questioning whether the Bush administration knew in advance that the attacks were going to take place – even suggesting that they were the ones responsible. I was intrigued. It seemed plausible. By the time I watched Zeitgeist, it was also apparent that the premise for the Iraq War was based on a lie. If they lied about weapons of mass destruction, what were the odds they would lie about 9/11? The third part of Zeitgeist claimed that a small cabal of international bankers really controls the world, using debt to keep us enslaved, and instigating disasters (including 9/11) in order to strip people of their liberties. The ultimate aim, according to the film, is to implant the entire population with microchips and create a one-world centralised economy and government to track and monitor every individual.

In 2008, the world was in the throes of a global financial crisis. The idea that rich bankers were scheming to keep us all in debt rang true to me, as I’m sure it did for many others who watched Zeitgeist at that time. After watching the whole film, I remember feeling empowered with this new information, like I had access to secrets that other people were not aware of. I remember feeling like a fog had been lifted and that many injustices about the world had been explained. My father had often told me that it was good to think outside the box and that following the crowd wasn’t always the answer. This seemed like the ultimate way to think differently. After Zeitgeist, I watched another slickly produced film called Loose Change. This one was solely about September 11 and built on many of the same themes outlined in Zeitgeist. Hearing the same claims made again reinforced the idea that something definitely didn’t add up about the official narrative of what happened that day. Thinking back, as much as I was sucked in by these films, it’s hard to tell whether they had an impact on the way I lived my life. I had friends who also watched them, and it made for some very deep and interesting conversations after a few drinks. I had always considered myself quite anti-establishment, and the themes of the films definitely bolstered that. I remember rewatching them a couple of times, but I never branched out much further beyond those two films. Fast forward to 2016. I had just finished a master’s in journalism and got a job with Storyful, a social media news agency. ‘Post-truth’ was the word of the year.

The UK had voted for Brexit, and Donald Trump was elected in the US in a wave of ‘fake news’ and conspiracy theories. The bread-and-butter work of Storyful journalists is to verify online video content from breaking-news scenarios so that news organisations can use it, safe in the knowledge that what the video shows is accurate. I was learning how to use online tools to do this, while also figuring out how to identify and track misinformation and conspiracy theories online. One day Zeitgeist popped back into my head, so I decided to give it a watch I started with part two, the 9/11 segment.

I was approximately six minutes into it when I heard a voice that I recognised. I shook my head and had a little chuckle to myself. It was Alex Jones, the notorious founder and presenter of InfoWars, one of the most popular far-right conspiracy theory shows on the planet. As a 19-year-old, I wouldn’t have recognised Jones’s voice, but 28-year-old me did. Zeitgeist, it turned out, borrowed quite a bit of footage from Terrorstorm, a documentary about 9/11 made by Jones the year before. Jones also happened to be listed as an executive producer on a follow-up film to Loose Change.

Jones’s involvement in both Zeitgeist and Loose Change raised huge red flags for me, and I started down my own rabbit hole to look into the claims made in the films. It turns out that jet fuel doesn’t have to melt steel beams for them to lose their structural strength. The ‘evidence’ the film used to suggest the towers fell in a controlled demolition was actually air and debris being expelled as the building collapsed on itself in a process experts call ‘pancaking’. Dozens of eyewitnesses at the Pentagon described seeing an aeroplane hit the building, none saw a missile. I could go on but it’s safe to say that almost all the claims they make have been thoroughly debunked by experts. Do I have all the answers to what happened on 9/11? I don’t. Do I still think it was an inside job? I don’t.

The claim that the US government was somehow involved in the events of that day was supported by all the other debunked claims, leaving nothing but speculation and suspicion to prop up the ‘inside job’ theory. It convinced me at the time, however, and it certainly convinced many others who continued down the rabbit hole from there. Since then, my work – at both Storyful and where I work now, a counter-extremism think tank called the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) – has been focused on understanding how disinformation (false information spread to deliberately mislead people), misinformation (false information spread without the knowledge that it is false) and conspiracy theories spread online, and how all these elements are weaponised by extremist groups and political movements. In many ways, the 9/11 truther movement provided a blueprint for how conspiracy theories would form and spread in the twenty-first century. People gathered in online communities, consulted bad experts, swapped evidence and ideas and did their own research. Amateur filmmakers took those ideas and turned them into easily digestible movie formats that spread far and wide in an ever-growing online ecosystem of truth seekers.

The Internet

When the Arab Spring erupted in late 2010, the power of the internet and social media was in full force for the world to see. Activists used Facebook and Twitter to spread photos and videos, gathering support and momentum for uprisings and protest movements that were erupting all across the Middle East. In 2013, after George Zimmerman was found not guilty of killing Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black boy whom Zimmerman had fatally shot for the crime of walking down the street, Patrisse Cullors tweeted using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, and a civil rights movement was born. In 2015, the #YesEquality campaign played a pivotal role in helping Ireland become the first country in the world to introduce marriage equality by popular vote.

Three years later, #TogetherForYes ran an equally successful campaign during the country’s referendum on abortion rights. The ability of the online world to bring people together is truly remarkable. The internet can provide sanctuary and can help people find like-minded others. Have a niche interest you want to explore? The internet has a community for you. In the early days of the internet, it seemed like we had finally discovered the tool that would strengthen democracy and bring us all closer together. However, just as the discovery of nuclear fission led to the invention of the atomic bomb, it became apparent quite quickly that the online world could also be utilised to bring out the worst in people. Since the early 2000s, online subcultures have exploded in popularity and birthed some of the most toxic movements the world has ever seen. Some within these communities have turned to terrorism, others have joined extremist groups or far right political parties, and countless others have dedicated their time to spreading hate and bigotry online in the name of ‘trolling’.

Others have become detached from reality and can no longer maintain relationships with friends and family members because of their descent down the rabbit hole of conspiracy theories. Although these groups once kept to their own fringe corners of the online world, in recent years their influence has penetrated the mainstream. It’s important to know how these communities evolved and the power they wield – both online and in real life.

‘Web of Lies’ by Aoife Gallagher, €15.99, is on sale now.

Make sure you check back in later this week to get an insight into the life, times and writing process of Aoife Gallagher with our Author’s Bookshelf…