Irish artist Bebhinn Eilish on mythology, mysticism, and unpicking misogyny through art

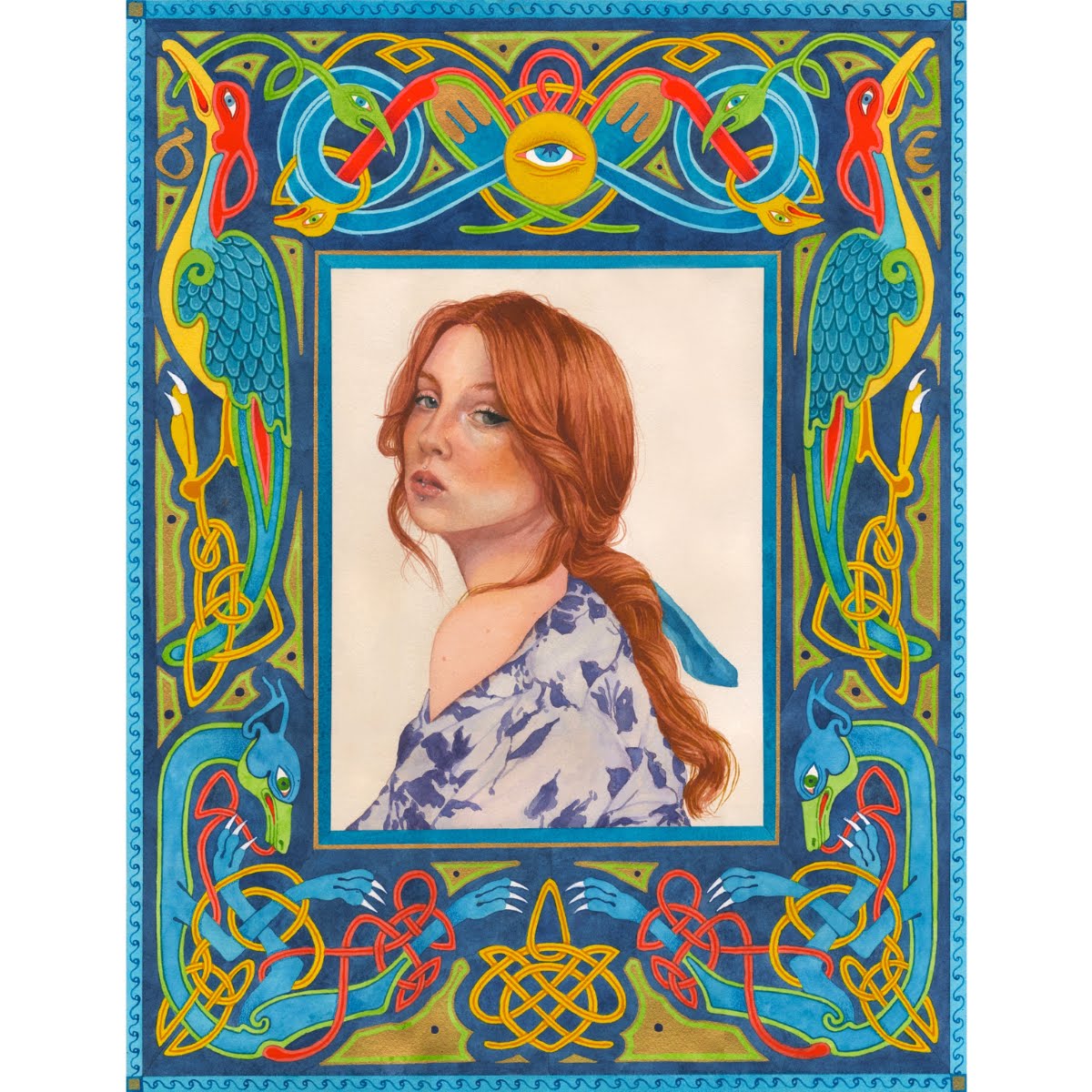

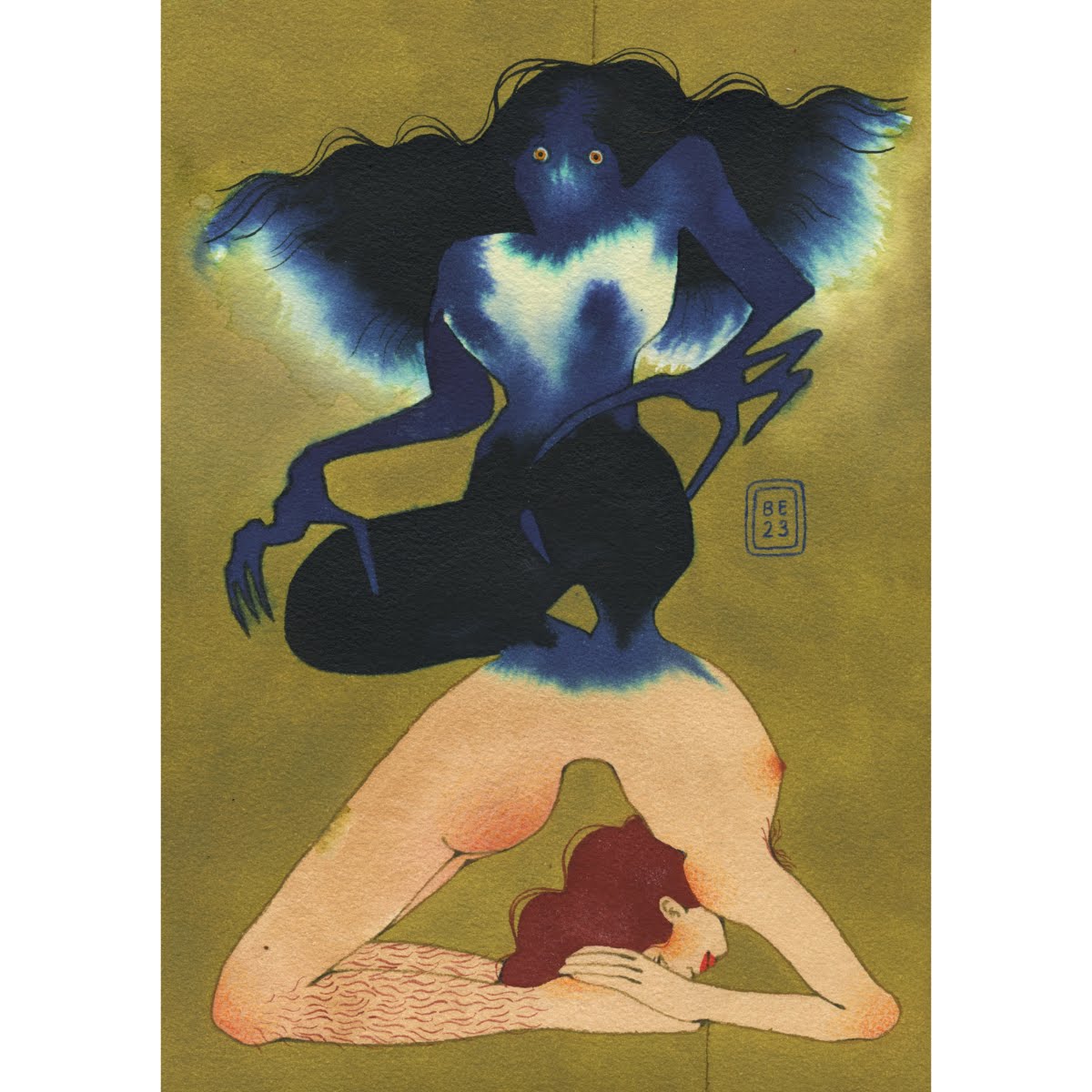

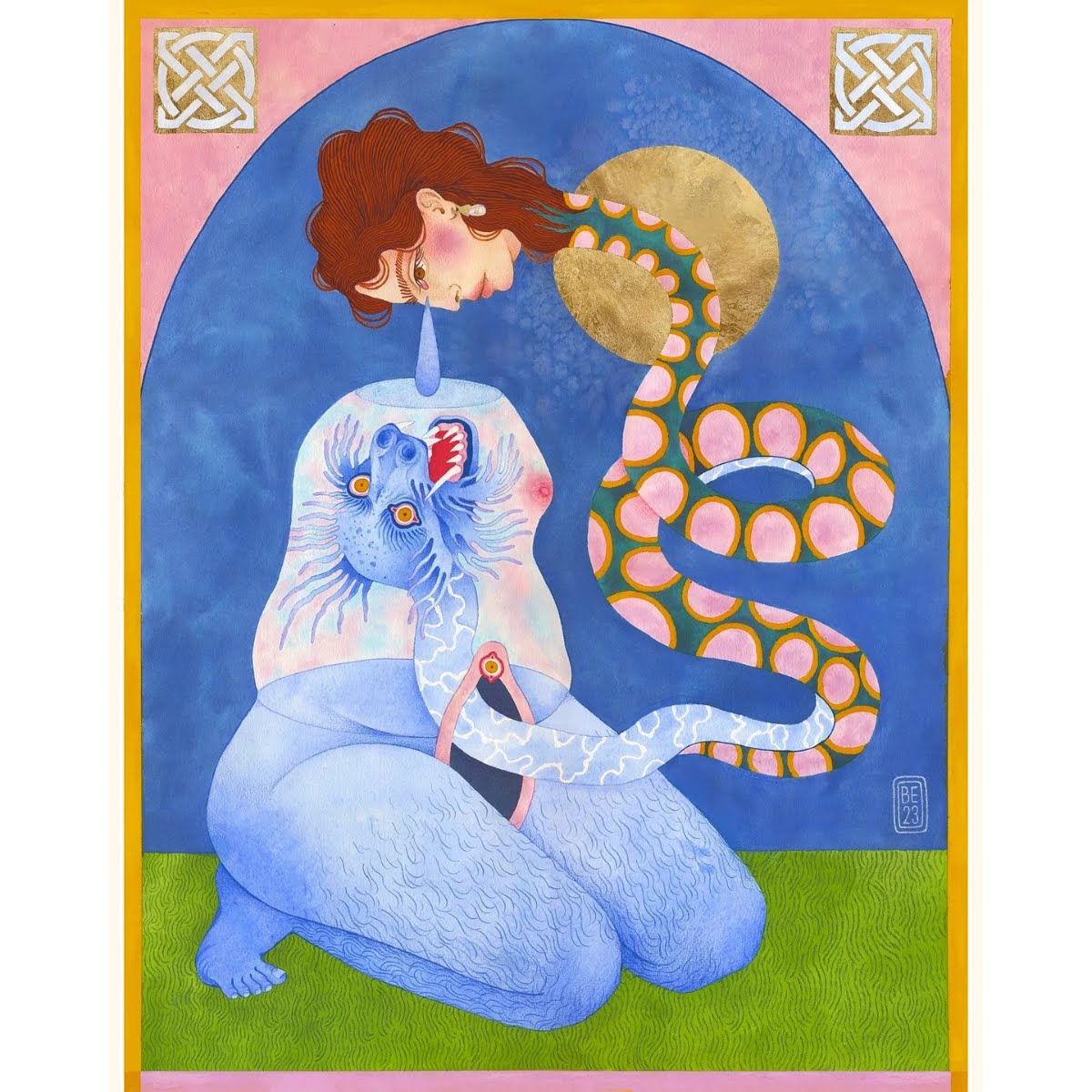

Bebhinn Eilish is an Irish artist and designer whose work centres around the female form and the many multitudes that exist within that.

Growing up in an all female household, taboos were something that did not exist in the world of Bebhinn Eilish. Empowered to reject shame, embrace femininity, and see the beauty and power in both herself and those around her by her mother, Bebhinn was introduced to the world of Irish folklore and Celtic mythology early on, all of which inspired and informed the art she would go on to create.

Realising that shame and stigma shrouds so much for so many, Bebhinn felt compelled to use her art as something of a resource for women in unlearning misogyny and stepping into their own divine feminine energy. Within her art, Bebhinn marries the uniquely personal with the collective consciousness, creating a modern and distinctive iteration of Goddesses and symbolism from Ireland’s rich past.

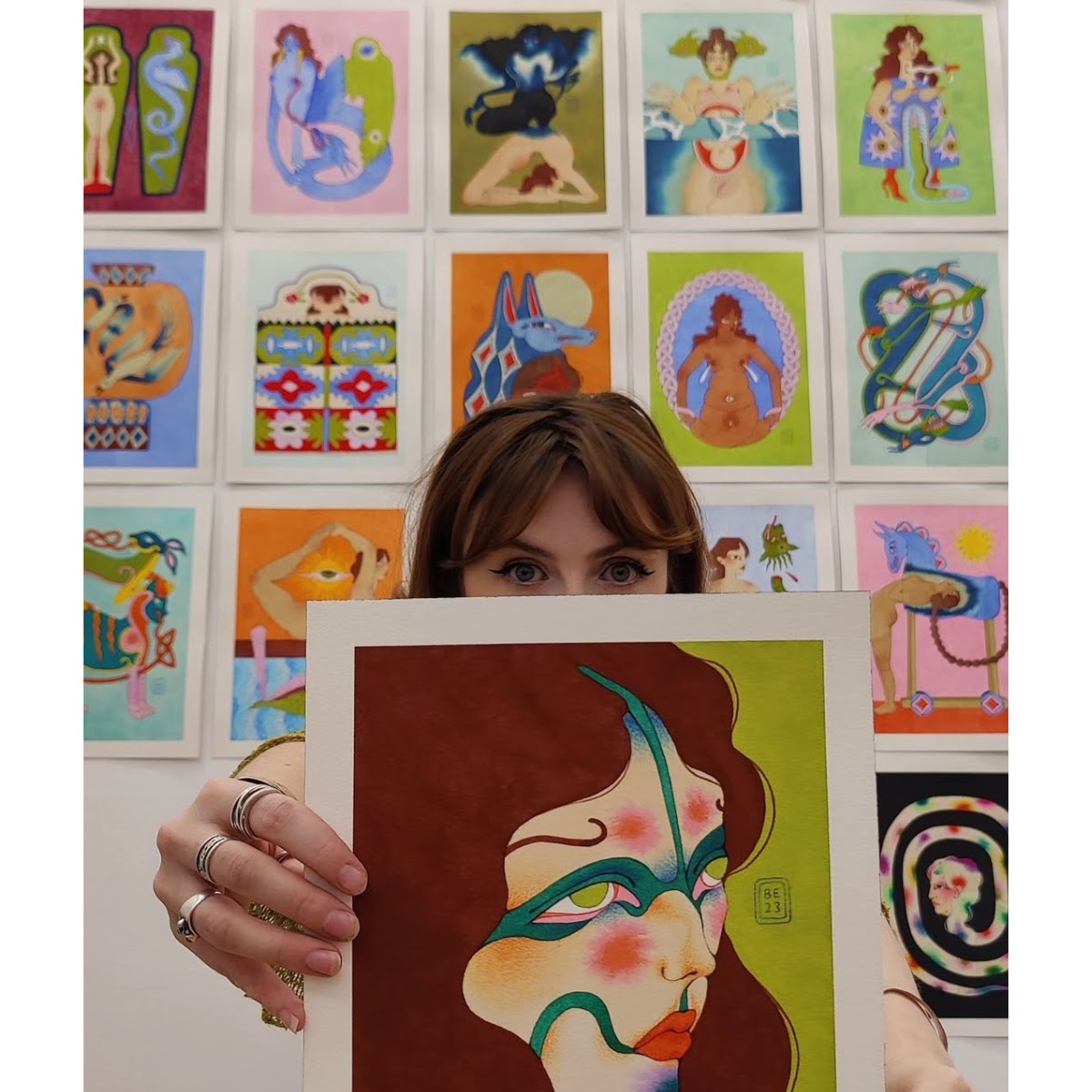

Selected as part of the Saint Patrick’s Day Festival’s ‘A Better City’ initiative, Behinn’s artwork will be displayed in an outdoor gallery exhibition on Crane Street. Celebrating joy, community, and culture, her designs will be featured alongside that of Claire Prouvost, Sophia Vigne Welsh, Mark Conlan, Ruan van Vliet, and Gavin Connell.

Ahead of the exhibition launch on Friday 15 March, we caught up with Bebhinn to get a little more of an insight into the realm of her art. From her favourite pieces of Celtic mythology to the ways in which her creative process has informed her own sense of personhood, Bebhinn expresses herself beautifully.

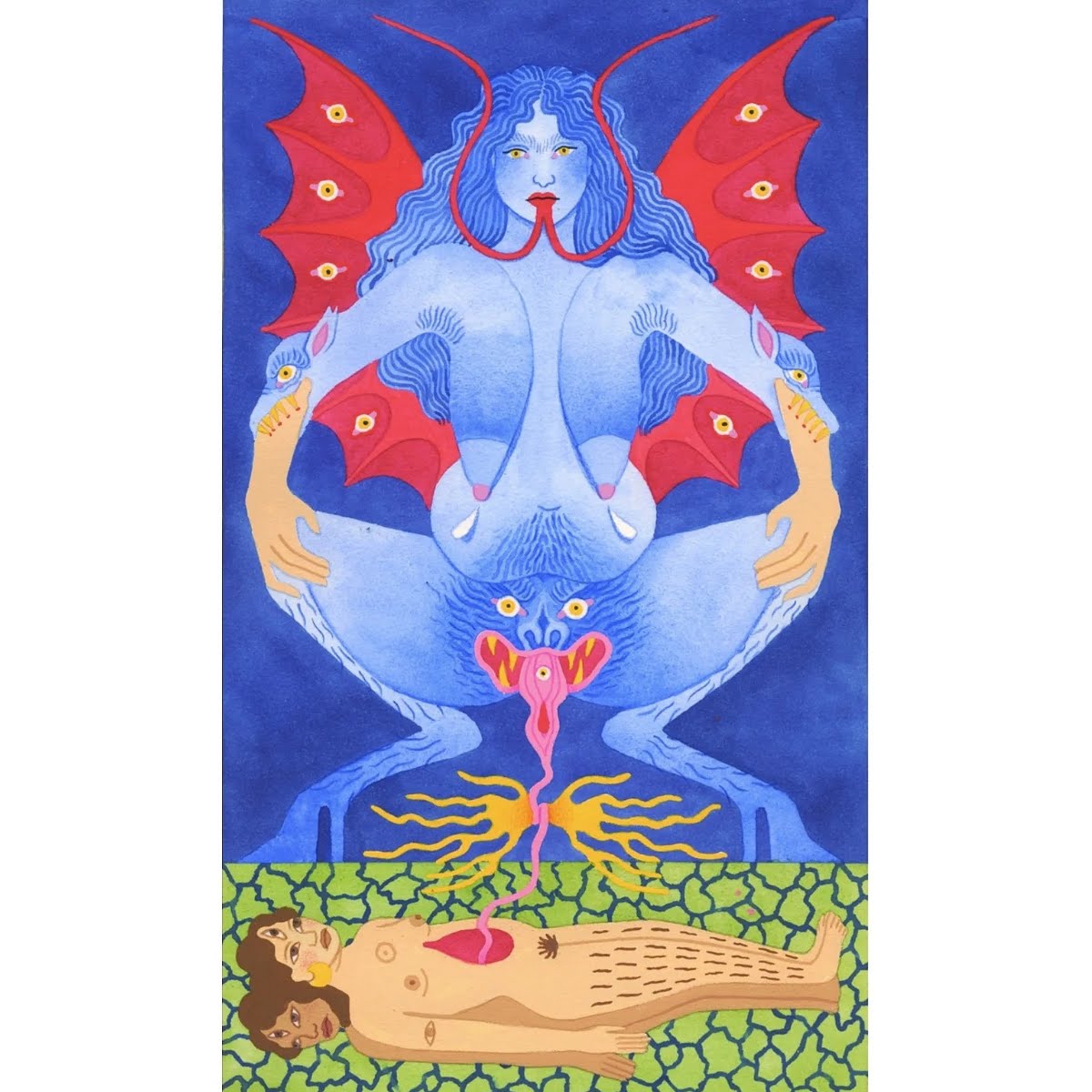

Your art deals with the female form and all the courage, strength, fragility and innate wisdom that’s wrapped up in womanhood. What drew you to explore taboos and transform them—body hair, stretch marks, masturbation, etc.—from stereotypically shameful subjects into pieces of art?

I think what drew me to them was the realisation that these are taboo subjects and that so many people in my life carried so much shame and stigma around these topics. I wanted to push them to question these narratives and beliefs and inspire them to see the undeniable beauty and power within themselves and in others, not in spite of these subjects, but because of them.

I was very fortunate to grow up in a fully female household where nothing felt taboo or shameful. My mother was an extremely strong, resilient, and supportive mother who has nurtured and inspired my artistic ability from the get-go. My relationship with my mam was, and still is, extremely special and empowering.

Realising not every person—particularly women—had these relationships, openness, and a ‘safe space’ to question and talk about these taboos with their family and friends pushed me further, to create art almost as a resource for women who are unlearning their misogyny and building stronger foundations for the future of women and women’s rights.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t until I lost my mam that these themes really stood out in my work. I see now how it was a direct response to my grief. My art is an ode to the feminine power that my mam bestowed upon me.

What message, or feeling, do you want your art to convey to those who see it?

Art, for me personally, can be a mirror. We usually resonate with a piece we find ourselves in. It never really matters the meaning behind a piece of work because people will interpret and take from it what they need. I’ve received countless messages from women all over the world who share with me their interpretation, and the importance of my work to them in relation to their life and their journey.

Common themes in these messages are about motherhood, even though I am not a mother. People share with me their experiences of child loss, birth, rebirth, death/grief, abuse, shame, the list goes on. Although the making of the art feels very intimate, personal, and ‘healing’ to my experiences, sharing it with others has made me realise our shared collective experience as women and how much my work has been used as a tool for women to question, explore, and appreciate themselves more deeply, more intentionally.

If I had to answer the question plainly, I like the idea of my artwork facilitating people in tapping into our collective unconscious, connecting us to ourselves and also something beyond. Creating esoteric art has happened naturally as my work has and continues to evolve.

Mysticism and mythology are also a huge part of your artistic style. What drew you to these areas in the first place, and how did they weave their way into your art?

Growing up I loved folklore and fairy tales. I loved how storytelling allows us to connect with and enter a realm beyond our own. When I was young, my mam used to read stories to me at night, a favourite of mine was George’s Marvellous Medicine by Roald Dahl. I remember feeling like I lived inside these stories, and the realisation that my imagination was a doorway into visualising these tales was definitely a starting point towards my fixation on mythology, symbolism and the power of storytelling through a visual medium.

My mam also held very pagan beliefs about the sacredness of nature and a reverence for the universe. Because of this, I have always had an inspiring sense of spiritual mystery that spurred my imagination and curious mind, making it really easy to find magic, even in the mundane.

Do you have a favourite piece of Celtic mythology?

Why make me choose?! There’s too much greatness in so many tales, but if I absolutely have to, I’d pick Bean Sidhe (Banshee) and Leannán Sidhe. When I was young, I was terrified of the Banshee and heard so many stories of her and people hearing her keening the night before a loved one’s passing. This eerie synchronicity is what drew me to her, and at the same time haunted me.

Leannán Sidhe, meaning ‘the fairy lover’, was once one of the Dé Danann (Danú’s children). When men looked to her, she was said to become the most beautiful woman they had ever seen and they would devote themselves to her, becoming so obsessed they would spiral into madness and ultimately die either by their own hand or by wasting away.

W.B. Yeats described her in his book Fairy and Folklore of the Irish Peasantry: “The Leanhaun Shee (fairy mistress) seeks the love of mortals. If they refuse, she must be their slave; if they consent, they are hers, and can only escape by finding another to take their place. The fairy lives on their life, and they waste away. Death is no escape from her.”

Having always been ‘death-obsessed’ since I was young, with many questions about the idea of the afterlife etc., the myths of the Banshee and Leannán Sidhe have stuck with me for the longest. Like my relationship with death and grief, these tales once terrified me, but now bring me endless inspiration.

You’ve been selected as part of the ‘A Better City’ initiative for Saint Patrick’s Day, where you’ll be choosing seven of your favourite Irish Goddesses to feature in your artwork on Crane Street. Can you tell us a little more about the Goddesses you’ve selected, and why Irish mythology and folklore is so important to Irish culture?

How gorgeous, I’m so grateful to have been invited to take part! Immediately I knew I wanted to depict seven Irish Goddesses, but it was not an easy pick, apart from Danu – the mother Goddess of all Celtic Gods and of the Tuatha De Danann (ancient Ireland’s magical race.) She’s featured in my work a lot and I feel her power really speaks to me. She is known as the Earth Goddess from whom all life emerged; she embodied the earth, rivers and sea.

Another two Goddesses I chose were Macha and Babd, thought to be two aspects of the tripartite goddess of war, death, and fate – the Morrigan. She is a powerful, all-knowing Goddess with the ability to bring doom to her enemies, but she is also a powerful ally if you can learn how to appease her.

The reason I chose to depict these Goddesses and why I think Irish mythology and folklore is so important is because of our colonial past. These legends, folklore, and mythical figures are a preserved expression of our beliefs, attitudes, superstitions, and a way of thinking as Irish people. Our folklore has stood the test of time in informing elements of Irish culture and heritage throughout history, cementing Irish national identity in an increasingly changing world; a changing Ireland.

I know you have a BA in graphic design, but what has your journey been like so far? Did you always have an affinity with art? How has your work evolved over the years?

I wouldn’t say I regret my design degree, but I definitely let others influence my decision when choosing what to study at college. Because I’ve always known myself to be an artist since early childhood, I rejected the idea of becoming a designer after I graduated. In studying graphic design, I really missed the tactility of art, and everything started to look like the same regurgitated designs.

Art was a lot more exciting. No brief, no client, endless possibilities and the variety of tools and materials – how could anyone not want to be an artist? I’ll never understand. Design has definitely benefited me though, and that’s why I don’t regret it. It taught me the power of critical thinking and problem-solving, the importance of self-discipline, and how to get my work in front of an audience.

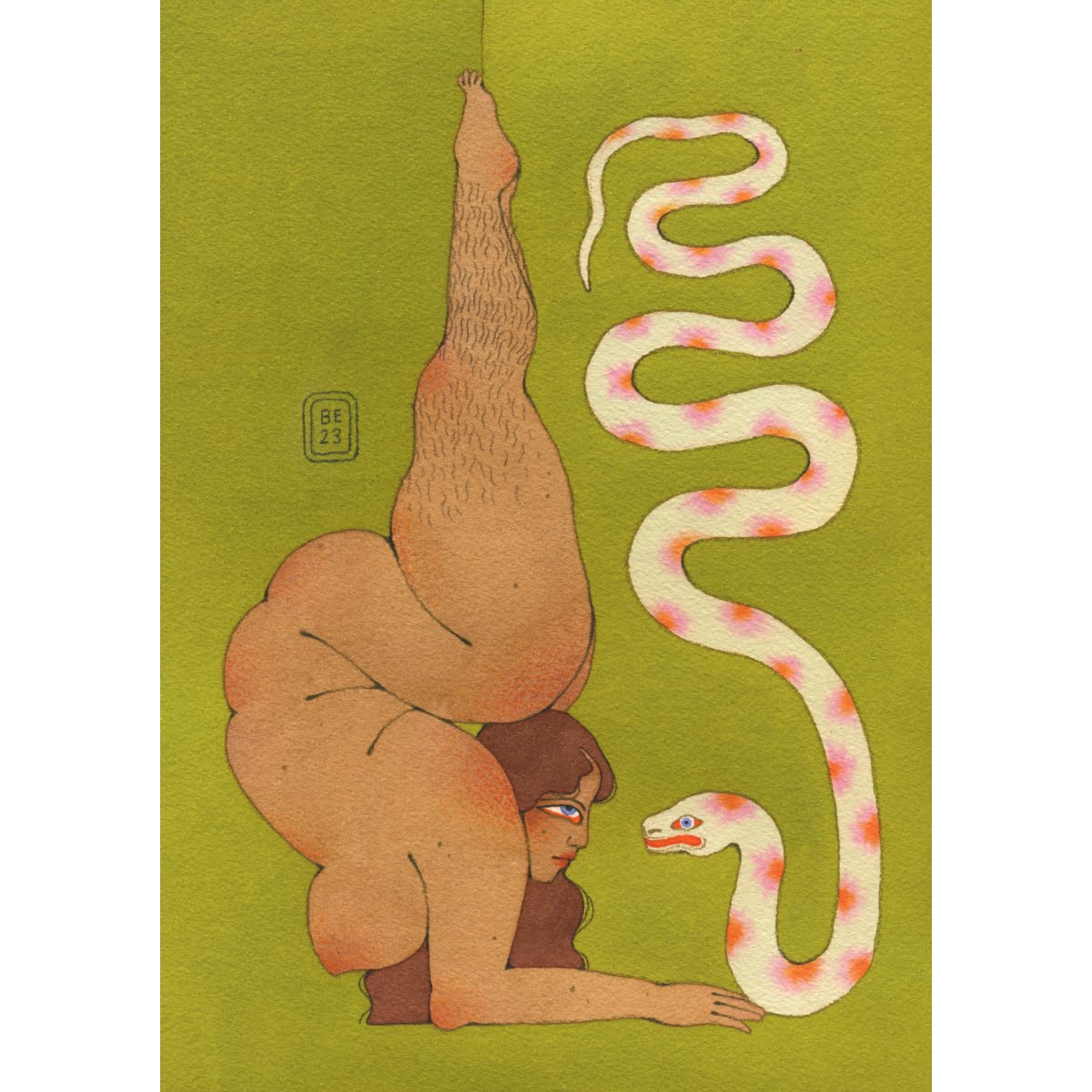

My artistic style has changed dramatically over the years and is constantly evolving. I work with so many different mediums and it has been fun exploring how my work will translate from watercolour into charcoal, for example. I also have so many projects and mediums I have yet to fully explore. It makes me really excited, and really impatient. I wish there was more than one of me!

How has your relationship with art informed your own sense of self and personhood?

Creating art has given me more purpose than anything else in my life. I’ve lived my entire life knowing that I was an artist, that it was the only thing in my life that would satiate me, although I never imagined my art would become what it is today.

The journey to, and the process of creating my feminist art has given me a stronger foundation when working through personal struggles and my evolving understanding of myself and what it means to be a woman. It is very much a reflection of my journey through womanhood, my findings, and what I have learned about our shared collective experience as women in a patriarchal world, built by men, for men.

My art process serves as a conduit through which universal taboos can be played with and explored. The truth is I don’t feel I have an identity beyond being an artist. If I wasn’t creating work or at the very least thinking about it, I struggle to imagine who I would be, or what life I would lead. Not that I’m not good at anything else, but nothing else makes sense to me.

Does making your passion a means of making a living make it less enjoyable in a way?

If anything, it’s a dream. How unbelievably fortunate am I to do what I love best and be able to sustain myself? I’m forever grateful and honoured to resonate with every person who supports my work, and those who don’t (they make my work that little more interesting!).

Although it doesn’t make it less enjoyable, being an artist is definitely not the romanticised life you see pushed out on social media. It can be disheartening, financially rocky and sometimes overwhelming, but that doesn’t take away from how fulfilling and rewarding it is.

What’s some of the best advice you’ve ever received?

It’s seen as a meaningless platitude to many, used to comfort someone or quite frankly to tell them to shut up worrying, but I’ve always liked the idea of ‘what’s meant for you won’t pass you by’. I’m a very excitable person and this is something my mam would reassure me of when dealing with episodes of mania or anxiousness. The idea that if fate intends you to have something you will receive it is actually something I believe.

That’s not to say you don’t have to work hard for what you want. My mam would also tell me that it’s when you’re most comfortable and content within yourself, when you really start to enjoy your own company that everything you have wished for will come to you. It also serves as a reminder in times of chaos to focus on myself, and nurture myself and my art. Everything else is secondary and if things go well, that’s just a bonus.

Who are some up-and-coming Irish artists and creatives we should have on our radar?

You interviewed Rohmie (RJaded Jewellery) before, but I can’t not mention her. Rohmie’s jewellery is so delicious, empowering and unique, I am so honoured to wear her ‘lucky Irish penny’ every day. Make sure to get yourself a treasure!

To name a few others; Wee Nuls‘ gorgeous feminist murals. Sorcha Francis Ryder‘s beautiful photographs; I am especially obsessed with her photos of one of my favourite bands, Lankum. I also want to shout out my partner Eoin James Quinn and his collaborator Colm Lennon who are currently working on Damascus, a short film about Freddie Scappaticci in the wake of his recent death and the Kenova report. I’m excited to see what these and many other contemporary Irish artists have in store for us next!

Bebhinn Eilish’s work features alongside artwork by Claire Prouvost, Sophia Vigne Welsh, Ruan van Vliet, Gav Connell, and Mark Conlan as part of St Patrick’s Festival’s ‘A Better City’ initiative, which aims to contribute to the revitalisation of the neighbourhood in Dublin 8.