Once a common feature of our town centres, homes above retail premises are lying vacant around the country, despite a raging housing crisis. What could be done to bring them back to life? Emma Gilleece investigates.

It is easy to forget that the unoccupied floors above our shops in our towns and cities were once homes. The 1960s saw the flight to the suburbs, with people lured by leafy front gardens and off-road parking. Today’s urban vacancy is particularly jarring during a housing crisis. To increase the supply of new homes the reuse of city- and town-centre floor space for residential use must be encouraged. What is stopping more of us from bringing back these homes?

Work with what’s there

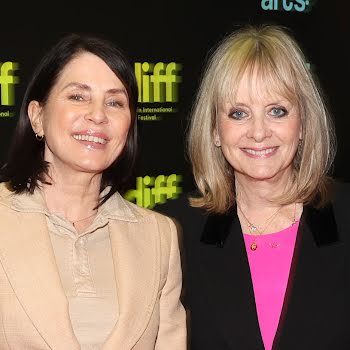

One advocate for living over the shop is conservation architect Ekaterina Voronova. Ekaterina recently converted into apartments two vacant floors above the Søstrene Grene store on Lower George’s Street in Dún Laoghaire, pictured on these pages. The client of this building contacted several practices, but it was Ekaterina’s approach which stood out. Her scheme was the only one which didn’t increase the height of the building by several storeys. Instead, her proposal was to work with what was already there. “It is one of the most interesting buildings in Dún Laoghaire,” Ekaterina enthuses, “[with] lots of craft treatment in elevation of the roof.”

Ekaterina converted the vacant upper floor premises under the “Bringing Back Homes” scheme introduced in 2018 by the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government. She retained the Victorian features of the façade of the building while creating a new doorway for access to two the apartments upstairs. At the rear, the architect added a bay window to the first-floor level and replaced the existing dormer windows at the second-floor level. Internally, the two floors, 100 square metres in total, were divided into small rooms and Ekaterina reconfigured the space to create two apartments, each with two bedrooms and a bathroom to the front of the building and a kitchen/living area to the rear. She also created a roof garden above the lower floor.

Both apartments are dual aspect, which was a delight for Ekaterina to work with. “I always think about light and how one feels inside a space. I liked the concept of a street out one window and the sea view out another.” Working with the high ceilings, she utilised internal glazing to bounce natural light through each apartment. She also did the interior design in a clean, modern, Scandinavian style, using natural finished timber in the kitchen units and flooring.

Challenges

Ekaterina constantly had to think about fire safety with this project, and had to add a new fire escape to the rear. For her, the rigidity of the fire regulations was a major challenge. “The regulations don’t tailor to something unusual. There should be a more custom-based approach,” she suggests. One thing Ekaterina wished to emphasise was the role of a good client and hers, in this instance, believed in her vision and problem-solving capabilities.

Another practice that has seen the changes in the last 20 years is Donaghy + Dimond Architects, founded by Marcus Donaghy and Will Dimond. Will took the plunge and purchased a terraced, three-storey premises built c.1820 in Francis Street, using the shop on the ground floor for the practice studio and returning the upper levels to a family home. A fourth storey was added to create bedrooms and a terrace, and a new bathroom was suspended from the rear wall at the half-landing between the two upper floors, thus allowing the original two-room-per-floor plan to be retained without subdivisions.

Will agreed that the fire regulations are restrictive, however inhabiting the building as a single dwelling can relieve the burden of compliance. Other potential challenges include accessing construction on tight urban sites, and working with adjoining owners.

Living over the shop is commonplace in other European cities so why not in Ireland? One major barrier Will theorised is the psychological one. Marcus noted the lack of awareness of the positives of living over the shop economically and environmentally, such as retaining embodied carbon in the existing walls, and the benefit of adjoining neighbours giving rise to a reduction in space-heating energy consumption.

Don’t be afraid of older

A fine example of a restored former living-over-the-shop premises that is publicly viable is the home of the Dublin Civic Trust, at 18 Ormond Quay Upper. Converting older buildings can be off-putting to some, their CEO Graham Hickey says. “There are many misconceptions about restoring old buildings, from ‘not being able to put a nail in the wall’ to the ‘red tape’ of the conservation process. In fact, Ireland’s system of heritage protection is arguably more flexible than those in other countries, being based around the concept of ‘special character’. No more than with a modern home, it’s vital to seek the right advice to ensure that upgrades are compatible with the traditional construction and special character of your home.”

The process of returning the vacant floors above our retail units is complex, but highly rewarding. The conservation architects, local authorities and resources are there to assist anyone with the courage to go against the norm to breathe new life into a former home-over-shop and thus our Irish town centres, making them distinctive, authentic and characterful places to live out our lives.

Photography: George Voronov