Page Turners: ‘The Alternatives’ author Caoilinn Hughes

Author Caoilinn Hughes discusses beloved literary titles, her writing process and creating memories through reading.

Caoilinn Hughes is the author of The Wild Laughter, which won the Royal Society of Literature’s Encore Award, and Orchid and the Wasp, which won the Collyer Bristow Prize and was longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award. She was recently the Oscar Wilde Centre Fellow at Trinity College Dublin and a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library. This year, The Alternatives was shortlisted for The Last Word Listeners’ Choice Award at the An Post Irish Book Awards and was a New York Times Editor’s Choice.

The Flattery sisters were plunged prematurely into adulthood when their parents died in tragic circumstances. Now in their thirties, Olwen and her three younger sisters – each single, each with a PhD – are leading disparate, distanced lives. Until one day Olwen, a geologist haunted by a terrible awareness of the earth’s future, abruptly vanishes from her home. Together for the first time in years, her siblings descend on the Irish countryside in search of a sister who doesn’t want to be found. In a derelict bungalow, they reach into their common past, confronting both old wounds and a desperately uncertain future. Fiercely witty, original and profound, The Alternatives is an unforgettable portrait of a family perched on our collective precipice, told by one of Ireland’s most gifted storytellers.

Did you always want to be a writer?

Writing became very interesting to me at about the age of ten. It didn’t become consistently important for another few years until reading became more central to my life and how I understood the world. By my mid-teens, I knew that writing was the thing. Reading and writing felt like spending time in the centre of the universe: everything else felt peripheral, or relational. My first published book was poetry, but since then I’ve mostly written prose—novels and short stories.

What inspired you to start writing?

Reading creates new memories—full, visual, emotional, irresolvable memories. Through reading, I get to have more than my own experience. I get to have more than my own capacity for change and wisdom and humour. Writing offers the same benefits, only more so: a story or a novel enlarges my life.

Tell us about your new book, The Alternatives.

The Alternatives follows four Irish sisters whose adulthood came early when their parents died in tragic circumstances. The eldest, Olwen Flattery, is a geologist who’s witnessing the collapse of Deep Time, with processes that should play out over millennia playing out over decades. The youngest, Nell, is a philosopher who’s been adjuncting for fifteen years at various Connecticut universities, while battling a mysterious illness she can’t afford to have diagnosed.

Maeve—a minor celebrity chef who lives on a houseboat in London—has carved out an unusual career navigating the food shortage crisis, only to wind up catering to elites. Rhona, a celebrated political scientist and single mum, fights for direct democracy while paying untold sums for seawall defences to protect her shoreside mansion from storm surges.

They’re all living distanced lives until Olwen, the earth scientist, suddenly vanishes from her job and home, and this disappearance brings the sisters together for the first time in years. So it’s a family reunion story, but also a story about women attempting to do meaningful, grounding work during an era of increasing instability and uncertainty.

The initial idea of the novel rested in Olwen’s character: the geologist. From meeting her, I knew that the book would be partly about women at work, women expressing themselves through their professions. I don’t think there are enough of those stories. I also knew that I was writing about someone who works in the arena of climate change, and about the people who love her: characters who are caught up in the existential ropes of the climate crisis.

Always, I’m writing about family, about how we individually and collectively think about the future, the limits and possibilities of adaptation. The novel is set now, so it depicts a society in crisis, reflected through the lives of these women—each contending with her own moment of flux.

What do you hope this book instils in the reader?

I don’t write with a moral agenda. I follow a book, rather than lead it. This allows me to live alongside the characters, without the detachment or foreknowledge of some god. I don’t think in terms of messages—neither as a reader nor as a writer—but I hope that the reader feels invested. Questions arise in the novel about whether or not self-sufficiency is a myth, and about what forms of care are essential. I hope that the reader has strong feelings in response to these questions.

What did you learn when writing this book?

So much! I couldn’t begin to say.

Tell us about your writing process.

For a novel, I usually have the feeling that there is someone waiting for me in the house next door. And I put off going there for as long as possible, I find other things to justify my putting it off (because it will be hard, no matter what!) but eventually, I know I have to get going.

So much of the novel will be in the first sentence. All I might know about the story itself is one of the characters; I’ll see them in a setting or situation. That, coupled with the sense of something being overdue. Committing to the first sentences is mammoth to me, because I write in one draft. I don’t do rough drafts. Afterwards, I edit. But that’s minimal, usually very little changes.

So finding the tone, temper and truth of the thing in the first sentences is key: you know it when you know it. I can put off trying to get those sentences down for months, or even years. But once I start, I’m committed to see it through.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

Every single thing I see and do and hear and witness and think about and feel and fail to understand. Every single person I meet. Every bird and post-box and film and plastic bag stuck in a tree.

What are your top three favourite books of all time, and why?

James Joyce’s Ulysses, because if I have to pick just three books, it has so many books within it, it grants so much license, and – crucially – it trusts the reader! Keri Hulme’s The Bone People because it’s an astonishing, virtuosic book, both in terms of the voice and prose and in the way it conveys isolation as well as communion. It also reminds me of the seven years of my life I spent in New Zealand. And for a third, the collected works of Shakespeare. Poetry and prose and drama in one!

Who are some of your other favourite authors, Irish or otherwise?

Virginia Woolf, John McGahern, Iris Murdoch, James Baldwin, Vladimir Nabokov, Tom Murphy, Franz Kafka, Clarice Lispector, Flann O’Brien, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, Dorothy Parker, Oscar Wilde, Anton Chekhov.

What are some upcoming book releases we should have on our radar?

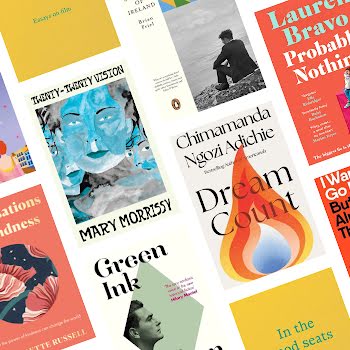

I’ve just read a proof of Garrett Carr’s The Boy from the Sea, which was very good. And I’m currently reading Seán Hewitt’s Open, Heaven, a queer coming-of-age. I always enjoy novels written by poets. I’m excited for Weike Wang’s novel, Rental House. And I haven’t yet read the recently-released Gliff by Ali Smith, but I’m saving it for Christmas reading. On that note – the new Winter Papers is out now. I look forward to it every year.

What book made you want to become a writer?

I’ll give you two things and halfway between them is possibly where I land! The sitcom, Father Ted… and Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s Selected Poems. Which I read over and over when I was in my early teens. I want to laugh and cry and have new thoughts when I read. The laughing is as important as anything else.

What’s one book you would add to the school curriculum?

Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman.

What’s the best book you’ve read so far this year?

I adored Carys Davies’ short novel, Clear. I also reread and was moved by Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. I thought James Hannaham’s Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta was a riot and a revolt and it should have won the National Book Award.

What’s some advice you’ve got for other aspiring writers?

Stop reading the internet!

Lastly, what do the acts of reading and writing mean to you?

Just this morning as I type this, Trump has been re-elected. If it weren’t for reading and writing, I don’t know what I would do. Reading and writing are how I understand the world, how I appreciate it, and how I make my peace with it.

The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes (ONEWORLD, €27.55) is on sale now.