Page Turners: ‘The City Changes Its Face’ author Eimear McBride

Author Eimear McBride discusses her most beloved literary titles, writing process and learning to accept that writing a novel never gets any easier.

An intense story of passion, jealousy and family from the trailblazing, award-winning Eimear McBride, The City Changes Its Face is her eagerly anticipated follow-up novel to The Lesser Bohemians, published in 2017.

It’s 1995. Outside their grimy window, the city rushes by. But in the flat, there is only Stephen and Eily. Their bodies, the tangled sheets. Unpacked boxes stacked in the kitchen and the total obsession of new love.

Eighteen months later, the flat feels different. Love is merging with reality. Stephen’s teenage daughter has reappeared, while Eily has made a choice, the consequences of which she cannot outrun. Now they face a reckoning for all that’s been left unspoken – emotions, secrets and ambitions. Tonight, if they are to find one another again, what must be said aloud?

Love rallies against life. Time tells truths. The city changes its face.

Did you always want to be a writer? Tell us about your journey to becoming a published author.

I’d been writing away ever since I was a child but, initially, I wanted to act. Losing one of my older brothers in my early 20s left me reeling and I knew things could never be the same again. I ended up spending a long, strange summer on my own in Russia and during it realised all the love of language that had been so central to acting would be put to better use on the page. That’s when I started writing seriously. There followed a few years of waking up early to get a few hours in before going to my temp job. At 26, I wrote my first novel, after which there was a long nine years of rejection. But with the backing and chutzpah of Henry Layte and Galley Beggar Press, A Girl is a Half-formed Thing eventually got published. I was 35 and that was the start.

What inspired you to start writing?

Reading. For as long as I can remember it was the very best part of my life. After a while, I started looking forward to having to write stories at school. Then one day it occurred to me that I didn’t have to wait for homework to be set, I could just sit down and write whenever I wanted to. So I ferreted out an old foolscap belonging to one of my older brothers, ripped out the used pages and set to work. I was six or seven then and I haven’t stopped since.

Tell us about your new book, The City Changes Its Face. Where did the idea come from?

I suppose it comes from the desire to know what happens next. If I’ve really fallen for a set of characters – whether in a novel, on TV, or in a film – not knowing how things work out in the long run drives me mad.

The book itself takes place over the course of one rainy night in Camden Town in 1996. Sitting in the kitchen of the flat they’ve shared for the last two years are Eily and Stephen (my earlier novel The Lesser Bohemians is about how they got together). She’s a 20-year-old drama student. He’s a 40-year-old actor. They both really love each other but are discovering that love isn’t the answer to every question. Plus they’ve had a few complications along the way. Stephen’s long-lost teenage daughter has reappeared in his life and Eily has made a couple of choices – some wise, some not – that have left their mark.

Although they can’t imagine not being together, all has not been well for a while, and this is the night when it finally comes to a head. So that’s the setup and The City Changes Its Face is all about what happens next.

What do you hope this book instils in the reader?

I’m not much of a one for trying to teach readers anything. What I want is for readers to take a little time away from their lives and allow themselves to experience what it’s like to be someone else for a while. Someone they may or may not like, someone whose choices they may or may not agree with. But to just be with them and see how that is. I want them to take Eily and Stephen as they find them and accept them as two flawed people with complicated pasts, trying to do their best in a difficult situation. If their story leaves readers with the impression imperfection can have its own value and beauty, then that’s the best I can hope for.

What did you learn when writing this book?

That writing never gets easier! Not even when you already know the characters very well. I expected A Girl is a Half-formed Thing to be hard to write – it was the first one, how could it not be? But I thought The Lesser Bohemians would be easier. It wasn’t.

It took years and the effort nearly killed me. Setting out on my third novel I was convinced it couldn’t be any harder. Strange Hotel, however, turned out to be its own crown of linguistic thorns. So much so that after it I thought ‘That’s it! No more novel writing,’ which lasted for about three years.

Then The City Changes Its Face started up inside me and I had no choice but to follow along after it. I still embarked filled with hope that this would be the one that would flow out of me in a great – and most importantly – effortless stream of creativity. But it was not to be, and this fourth novel ended up being one of the hardest so far.

Now I’ve arrived at the conclusion that each novel is its own war. Each brings its own frustrations and involves different sacrifices. Each requires new strategies and inflicts its own special kind of suffering in order to win through all the self-doubt and critical voices roaring away in your head. Maybe what I learned is acceptance. In life, some things just take what effort they take because they have to be the way they are, and no amount of moaning is going to change that.

Tell us about your writing process.

Like most writers, I’m very disciplined about putting the hours in. I aim for 9am to 5pm but it’s usually a little less and I never know when it’s time to start a new novel. I just get a weird impulse to write. So I never plan ahead and I never know what a novel will be about when I start. I used to think this was a time-wasting flaw but then I realised that finding out what’s going to happen is actually part of the process. If I already knew how the story was going to end, why would I bother going to all the trouble to write it? That said, I do keep a very active eye on the logic so nothing inconsistent with the character starts to creep in. Incongruous behaviour or dialogue are serious mistakes and novels rarely recover from them.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

I hope for inspiration but in reality, I don’t bother much about it. Experience has taught me that work comes from work. Far more important than inspiration is concentration. When you get yourself to the right level of concentration, connections begin to reveal themselves in unexpected ways. Problems clarify and characters reveal hidden facets which can radically change the direction in which the story is heading. For example, the film section in The City Changes Its Face ended up being so extensive because I realised that cutting in and out of it – as I first thought I would – was cheating. Logic insisted I had to write it in its entirety with no shortcuts. I slightly despaired when I realised how much work it was going to be but I’m glad of it now. So ‘thinking hard’ is probably as close to inspiration as I get, I’m afraid.

What are your top three favourite books of all time, and why?

This is an impossible question to answer. Of all time? My reading tastes have changed so much throughout my life, and I’m being changed by what I read all the time. So instead I’ll say, at this moment – and for a long time before – these books have been important to me.

Ulysses by James Joyce because it’s obviously the greatest novel of all time and, quite literally, changed my life.

The Devils by Dostoevsky. It’s not even his best novel but it’s been a huge imaginative influence on me. I love the idea of the secret within, which once revealed completely alters the readers’ perception of a character.

Anna Karenina by Tolstoy because I love a female protagonist who refuses to be a morality tale. She outwitted her genius creator’s attempts to make an example of her and has instead become a symbol of women’s struggle against oppression ever since.

Who are some of your favourite authors, Irish or otherwise?

Well, the three above never age or wear out. But I also love Thomas Mann, George Eliot, Edna O’Brien, E.M Forster, Milan Kundera, Bohumil Hrabal and Cormac McCarthy. This is a list that could go on and on…

What are some upcoming book releases we should have on our radar?

I think We Pretty Pieces of Flesh by Colwill Brown is going to get people very excited so keep an eye out for that. Tales of errant girlhood never lose their attraction especially when the writing is as inventive as it is here.

Also Nova Scotia House by Charlie Porter. A truly original debut about life, life in the shadow of death, the struggle to find one’s place in an unforgiving world and the long legacies of both callousness and love.

What book made you want to become a writer?

Maybe Anne of Green Gables. I read it when I was nine, just after my father died. Her combination of wilfulness, imagination and romantic escapism made a deep impression on me at a time when I also wanted to escape harsh realities for more beautiful, invented worlds.

What’s one book you would add to the school curriculum?

Primo Levi’s If This is a Man. Now more than ever we need to be reminded to relate to others as people and as individuals with complex histories and reasons for being who they are and thinking as they do. Mob think has become incredibly active again, right along the political spectrum, and Levi reminds us of the terrible human consequences of not asking more of ourselves as individuals. Kindness is all very well but uncomfortable acts of unfashionable empathy could really do with making a comeback.

What’s the best book you’ve read so far this year?

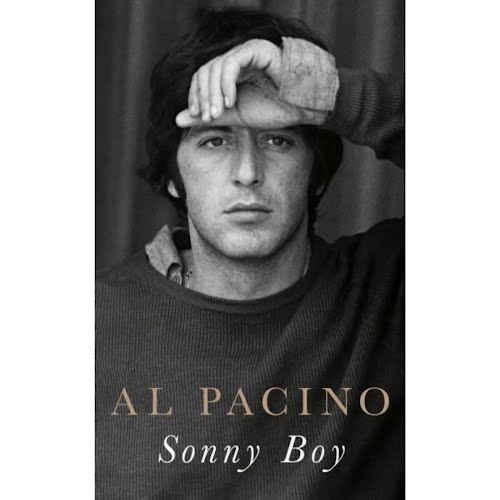

Al Pacino’s memoir Sonny Boy. I like autobiographies generally – people offering their own whys and wherefores for what’s gone on in their lives. Pacino has long been one of my acting heroes and I particularly loved reading about the struggle of growing into the artist he became from such unpromising beginnings. The failure. The success. The determination to continue but also the need to protect his talent and his sanity from expectation. Then how that creative inner world deals with being slammed against an outside world in which the money people need to be persuaded your little art project is worth taking a chance on.

What’s some advice you’ve got for other aspiring writers?

Don’t waste your time aspiring, just get on with the doing. This is the only thing you will ever be able to control in the literary world. Demand a lot from yourself, don’t make excuses and don’t take shortcuts. Then, whatever the reception – be it failure or success – you can stand by what you’ve made. Sometimes that will be your only reward, but it’ll still be better than knowing you’ve compromised or taken the easy way out.

Lastly, what do the acts of reading and writing mean to you?

Writing means space, thought and sanity. Reading has always meant access, although that access has taken many different forms over the years. As a child, it was uninhibited access to the wildest realms of imagination. As a teenager, it was access to the world, to people and places I didn’t know and concepts I had never heard of. As an adult, it’s grown to be more and more about access to the universal. Those places of shared humanity and vulnerability that are so often hidden beneath the public peacocking of opinion and identity. Increasingly, it has also become one of the few remaining private access points for unmediated experience. It’s just you and the writer, with no one else around warning or advising what you should be thinking or feeling about what you’re experiencing. Frankly, it’s my idea of heaven.

The City Changes Its Face by Eimear McBride is published by Faber.

Portrait photography by Kat Green.