Pray For Our Sinners: Director Sinéad O’Shea on her deeply moving (and surprisingly uplifting) new documentary

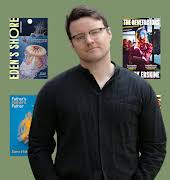

Already with one feature-length film and a narrative short under her belt, Irish filmmaker and journalist Sinead O’Shea was trying to find her next project when a conversation with an old school friend brought her focus closer to home… and thus, Pray For Our Sinners was born.

Set in her own hometown of Navan, O’Shea’s latest documentary is a remarkable account of Ireland’s recent history of brutality against children and women touching on topics ranging from corporal punishment to state-sanctioned mother and baby homes. Exploring the impact that the Catholic Church had on the country at large, the film features first-hand testimonies from local men and women; revealing the plight of unmarried mothers; the inconceivable horrors of mother and baby homes and the ubiquity, almost normality, of violence against children in Catholic schools.

“I’ve done some tricky things in my work before, I’ve gone undercover in places like Iran and Eritrea and spent five years shooting in quite difficult circumstances in Northern Ireland for my first feature, A Mother Brings Her Son To Be Shot. Yet, making a film from my hometown has been my most challenging project to date,” Sinéad admits.

And yet, despite its heavy subject matter, it’s surprisingly uplifting. A handful of remarkable figures were brave enough to resist the status quo; two women who refused to give their babies up for adoption, a 9-year-old boy who dared to speak out against his teachers’ physical abuse; and a married couple, Mary and Paddy Randles, who set up a family planning service and campaigned for the abolition of corporal punishment. Their stories prove there’s truth in the age-old adage that not all heroes wear capes – they’ve suffered unimaginable hardship, but they’re still willing to stand in the light.

Here, Sinéad talks to Sarah Finnan about this deeply personal project and how it can be tough to express critical things about the people and places you know well.

What made you want to tell this story?

Well, I suppose, I come from Navan… even though I do slightly feel like a fake Navaner at the moment – I left there when I was 17 and that was years ago – but I always kept in touch with a few people. I was trying to think of what I would do next, when a school friend said to me, ‘You should look into Mary and Paddy Randles and the work they did around corporal punishment.’ She told me the bare bones of that story. It was a big surprise that anyone was standing up to the church in those days, but I wasn’t sure if you could get a whole film out of that story. Around the same time, the mother and baby home report came out. Mary said to me, ‘The report is so shocking, especially when I think of all the young women who used to stay here, who used to be in hiding from the mother and baby homes.’ And I was like, ‘What!? Hold on now Mary, you’ve never mentioned that before!’ So, that was kind of the beginning of turning it into a feature film because I knew we had other elements to add to it, like Mary’s work with contraception. She’s such a modest person, it was, like pulling teeth sometimes! She hates any sort of labelling or any kind of triumphalism at all. So, you know, I’d say things like, ‘That was a resistance’ and she was always like, ‘No, no, no. It was just common sense.’ So, it’s really beautiful that type of heroism, the type of heroism that doesn’t draw any attention to itself.

I’ll be honest, I was expecting this documentary to be a very hard watch – which it definitely is at times, but there’s an unexpected hopefulness there too. All of the people you interview throughout have suffered great hardship but they’ve chosen to stand in the light. What was it like to hear them tell their stories?

It was very interesting, especially to see the contrast between the men and women I interviewed. Norman was just desperate to tell his story. Whereas Betty, you know, she was much more tentative. I think it just made such a huge impression on her all those years ago, the way that the nuns treated her, the way they kept telling her that she had something to feel ashamed about when, of course, she has nothing to feel ashamed about. But you know, it just really impacted her.

This documentary is so important because it’s finally going against the culture of secrecy and shame that took advantage of these women back in the day. Was it hard to convince, or perhaps I should say encourage, people to be involved?

I think to be truly honest, none of the participants would have been so happy to speak to me if it wasn’t for their personal relationship with Mary. They love Mary and they felt such gratitude towards her that they really wanted to help this film be made. I suppose they feel they owe her something, you know. Yes, there’s hardship in this story, but there’s actually something positive, there’s actually a sense of victory for once. So, I guess that’s why it was easier for them to share some of their stories.

There’s a scene where you mention that as a child, you were kept up at night thinking about hell. I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie Belfast, but it reminded me of how the young protagonist, Buddy, is conflicted by what he’s heard about religion too. A lot of the messaging when we were younger was very harsh and scary, was that your experience?

I think conflict is the right word for it. This film isn’t necessarily anti-Catholic, you know, it’s quite nuanced, but I agree, I think the way in which religion was taught in schools was unnecessarily harsh. It’s not that useful to tell children that they could be struck by God for doing something bad. Sure, you might get a little bit of good behaviour out of them in the long run but that’s very inhibiting, and it’s very frightening. Obviously, I don’t like that aspect of religion, but I suppose the conflict comes in that I can recognise that there are a lot of very beautiful ways of teaching behaviour through Catholicism too. It’s a wonderful thing to be a moral person, it’s a wonderful thing to say ‘I will do onto my neighbour as I do onto myself’. All those aspects of religion are very powerful. Even just the idea of studying and reading books for some time every day, you know, books about morals and ethics. I suppose ultimately what I’m trying to say is that there is definitely a conflict – these ideas of hell for eternity, that is an awful concept to teach small children. Or the idea of limbo for unbaptised babies, purgatory… they make such a deep impression on you as a child. But there are beautiful aspects too and I guess Fr. Farrell who you hear a lot about throughout this documentary, he really represents those contradictions.

You mentioned there that this is quite a nuanced view of Catholicism. The ending where you talk about Fr Farrell made me think of that Walt Whitman quote, “I contain multitudes”. It’s something that I think we’ve been seeing a lot more of on TV and in films – characters that are both good and bad, people that show humanity exists on a spectrum. Even Betty is unwilling to condemn Fr Farrell for his part in things. Why do you think that is?

I just think he is, in his way, just a typical priest. You know, there’s been an awful lot of focus on very depraved priests, paedophile priests – and rightly so – but actually, I think for a lot of people, their experience of a parish priest was someone a bit more like Fr. Farrell. He was a brilliant man, he was kind and clever and brave, but he also did things which are just completely in line with a church that doesn’t care enough for women or for children. He drove Betty to a mother and baby home, he encouraged people to turn a blind eye to corporal punishment – yes, he does these things, but he also helped the workers strike and form their own collective. He talked about socialism, he talked about people helping the poor, and he really meant it because his actions supported those words. He represents probably the best and the worst of Catholicism at the same time, and I really like him as a character.

I know personally, my relationship with religion has changed greatly over the years – hugely shaped by the many atrocities that have been uncovered. Would you say you’ve had a similar reckoning?

Yeah, I guess. I suppose it was probably lots of things coming together. I was quite a naive little girl, you know. I would pray very intently every night. I’d have these old rituals where I would say all these prayers, but if I made a mistake, I’d have to start all over again. I was very conscious of God being around and God’s voice was there and I was talking to him. But I always found mass quite boring, I have to say. When the opportunity to not go to mass came along, I was like, ‘Great! I’m not going to go.’ But it took a long time for me to shed the idea of God. I’m probably like most people in that if someone gave me a bit more proof, I’d be like, right because you know, you’d love there to be a heaven! Christmas is so beautiful Easter, like I remember on Good Friday, you know, when Jesus had died but then the joy of Easter Sunday. I would never be so rude as to condemn religious people, there’s just so much beauty to religion.

I’m from a small town myself, so I know it can be hard to tell small-town stories like this without backlash. What has the reception been so far?

We’ve only screened once so far in Ireland. It’s been shown in quite a few places in America, but it’s been shown at the Dublin Film Festival. So quite a few people from Navan came up to see it. They all really liked it but they were all people who, I suppose, had gone out of their way to see the film so it might have been a bit self-selecting. We’re having our first screening in Navan on April 18, so I’m quite nervous about that. I do think things have come a long way. It’s funny for Mary Randles, it’s been such a journey for her. She arrived in that town and she was like, ‘It’s so insular’, and now she loves it. She wouldn’t leave it for all the tea in China! She frequently goes out to her porch and people have left presents there for her. People love her and she loves them so I think whatever people might say about, the depiction of Fr. Farrell for example, I think everyone will just be very proud of the Randles and how they were portrayed. I think that will be a source of pride for the town, I’m not sure about the rest.

As you yourself note, Irish people are on a journey to recover from this. This happened in living memory and the people of Navan are still dealing with the trauma of it. What needs to be done to help that healing?

I don’t know. I mean, I feel like me saying these things is probably a bit irrelevant, but I do think the church needs to move away from its ownership of so many of the primary and secondary schools, and I don’t like how the church has such controlling stakes in a lot of our health institutions. I don’t like what happened with the National Maternity Hospital. More generally, I do think for people, you know, even for younger people in their forties, there is a lot of trauma there regarding how the church interacted with state against its people. And I think maybe some kind of Truth and Reconciliation forum or some kind of transitional justice model needs to be deployed. Not for any kind of financial compensation, but because I think people might need some acknowledgement of what they’ve experienced. More particularly, I do think the redress fee for the mother and baby homes should just be dumped. I think it’s so tragic and so sad that someone like Betty is only entitled to the smallest payment. It’s such a distortion of what a compensation scheme should be. It’s so insulting too, you know these women spent a lifetime being told that they should be ashamed of something and then the very people who are supposed to be helping them at the end, have done the same thing. It’s really sad. Obviously, you’re always hoping with a film like this, that it will help create talking points, but you know, maybe that’s too ambitious.

What would you like audiences to take away from this film?

That it’s not actually a miserable film! All of the women are so brave, they’re just such amazing women and how they stood up to a system that just did not allow you to do that. It’s easy nowadays to be on social media and to have your Instagram lives and have a stance, but to do what they did, that was real bravery. I just admire them so much and I wonder, would I have been so brave. There is weight in the bad apple theory – that a bad apple can ruin a whole barrel of apples – but similarly, a good apple can impact so many others. The Randles, they had such a positive impact on so many people around them. A lot of the stuff I make is quite miserable so it’s so nice to do something with people who are saying something positive!

Pray For Our Sinners will be released in Irish cinemas on April 21.