Step inside artist Anita Groener’s Dublin studio, full of tiny, beautiful things

From a home studio in Glenageary, Co Dublin, visual artist Anita Groener works with silhouettes and twigs to create intricate dioramas that explore the theme of displacement.

When visual artist Anita Groener planted birch saplings in her Glenageary garden 25 years ago, she couldn’t have imagined that they would become a fundamental part of the work she makes today.

“I never thought I would work with twigs,” says the Dutch-born artist as she shows me around her garden on an unseasonably warm autumn day. “And when I started working with them in 2015, I never thought I would get such mileage out of it.”

Groener, who moved to Ireland from the Netherlands in 1982, is a passionate plantswoman whose garden is blooming with plump hydrangea, potted verbena and bursts of crocosmia on the day of my visit. But it’s at the end of the garden where the magic happens. Here a silver birch and paper birch bookend her recently built workshop-cum-shed. The statuesque trees add structure to the garden but they also provide Groener with the medium with which she now works.

“I used to do different installations with paper silhouettes, which I still use,” she explains. “I wanted them on the wall in a pattern, and I wanted them to disappear, but I was wondering how I would get them to disappear,” she recalls. “I was staring out the window and I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll try a twig’. I glued one on a twig, stuck the twig on a wall and since then I’ve made all these enormous installations.”

The mother-of-two began to explore the theme of displacement through her work during the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis. “I was gripped by what I saw on the news,” she says. “These people had good lives and yet something like this could happen to them – and it’s still going on.” Motivated to help, she considered volunteering in Greece, “but then I thought my responsibility lies in my work as an artist. I felt compelled to respond in my work, partly because I’m a mother and I feel I’ve produced the next generation; and as a citizen, I felt I had to do something.”

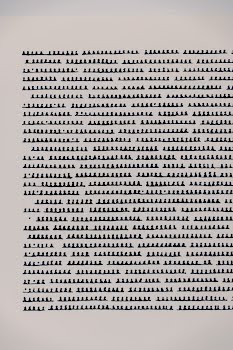

Her first piece, which would become part of the Citizen exhibition shown in the Butler Gallery, began with her researching thousands of images of refugees walking with their luggage. “The scale I used at the time was 2.5cm, so from a distance they looked abstract. I use beauty to entice people to have a look. People literally walk up to the work and they see, ‘Oh my god, these are people’. And it’s important that they are seen as people. They are more than refugees, which is a label.”

Groener wanted the work to appear abstract from a distance “because we can’t fathom what is going on” when people are displaced by war. Balancing the silhouettes along delicate twigs also challenges viewers’ perspective. “They disappear when you stand in front of them and you see them as you move. It’s a play on you deciding if you want to see them or not.”

Over the last few years, Groener has experimented with various twigs. Birch twigs, which are especially pliable, are used in most of her work. She also uses reeds and plans to work with sanguisorba after fellow artist and gardener Terry Dunne suggested it for its delicacy and rigidity.