Irish teenagers are leaving school with little understanding of how their bodies work

The experts weigh in on the key facts every secondary school student in Ireland – of all genders – should be learning about fertility.

A few months ago, we conducted a reader survey on the topic of fertility, and one issue kept cropping up in the comments and feedback given by readers – that they wished they’d known more about their natural fertility from a young age, with many expressing a desire that it be taught in schools going forward.

Irish teenagers learn about contraception, human biology and how babies are born. But the message is still predominantly focused on how not to get pregnant. There’s very little information shared on related topics like fertility challenges, the narrow window of ovulation, IVF, endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or male infertility. This academic year (2021-2022) has seen the implementation of some key amendments to the national curriculum for relationships and sexual health in Ireland for the junior cycle and there are further developments in the works for senior cycle and primary level, but it’s unclear as to whether the topic of fertility will be covered in-depth.

Introducing a more diverse sexual health education is not a new concept – in fact, according to the European Atlas of Fertility Treatment Policies published in December 2021 by Fertility Europe in conjunction with the European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, both Armenia and the UK have introduced a state-organised fertility education programme that teaches young people about fertility care and challenges.

Fertility Europe, with support from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, is working to improve fertility awareness and advocate for reproductive health education in schools across the continent through its Fertility Awareness Project. According to the organisation’s website, fertility awareness is “a level of knowledge and awareness of society and its various subgroups on the topic of the human reproduction system and life cycle, as well as the possible threats to reproductive health and the ways to protect it throughout the stages of life.”

And for those who are thinking teenagers already know about human reproduction, consider the fact that just five years ago, three fifth-year students in Roscommon Community College (Simon Leonard, Michael Egan and Conor Lavin) presented a study for the 53rd BT Young Scientist and Technology Exhibition entitled “Insight from a New Generation – Fertility Issues”. They examined students’ and adults’ awareness of factors that affect fertility and concluded that their peers lacked a real understanding of the factors that affect both male and female fertility; specifically, 79% of participants in the study didn’t know an egg can live for only 24 hours after it’s released from the ovary, and 54% were not aware of the optimum time to conceive.

The Knowledge Gap

Deirdre Betson, sexual health educator, campus nurse at Technological University Dublin Blanchardstown, and founder of SHARE (Sexual Health and Relationships) Ireland, believes that in order to learn about the many causes of fertility issues, people need to have a good understanding of sexual health. “So many people are suffering in silence because they never knew [fertility challenges] could happen to them.” Having personally gone through miscarriage, infertility, IVF, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) abroad, a C-section birth, and international adoption, Deirdre is perhaps as equipped as anyone can be to offer an informed opinion on the subject of whether we need to improve our education of young people on the topic of fertility. “It should be far more comprehensive, and far more objective. I went to Catholic school myself, and sex education was practically zero. We literally just got the male and female anatomy, and that was really it. And now, there’s a whole cohort of parents who just didn’t have that education, and are rearing teenagers – how are they supposed to inform [their children] if they didn’t get that education?”

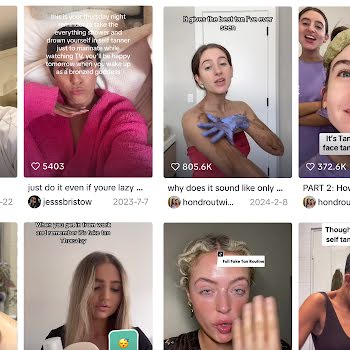

“There isn’t that emphasis on bodily autonomy, and being comfortable in your own skin and getting to know their bodies,” Deirdre continues. “Infertility is never mentioned. It’s very much a one-size-fits-all of reproduction. Your mucus changes throughout the month, and it can be very indicative of when you’re actually ovulating, but young women aren’t taught that at all – how to read their own bodies, and what’s normal for them. The focus is on ‘don’t get pregnant’. If you don’t educate [young people about their fertility] they cannot make their own decisions about it. They need to be in control of their own bodies, they need to be comfortable in their own skin. Like with mental health, we need to break down the stigma around sexual health. We need to give young people as much education as possible so that they can make informed choices themselves and know where to get the proper resources and objective information.”

Deirdre also emphasises that male fertility issues can be better controlled when young boys are more aware of what they can do to protect their fertility. The blow experienced by someone when they learn their chances of conceiving are lower than hoped might not be so shocking if some level of previous fertility knowledge was there beforehand. Furthermore, when we as a society have a greater understanding of the various issues people can face with regards to fertility, we might be more sensitive in the language we use around those who may be going through that difficult process in silence.

Fertility Education

Mary McAuliffe is the head of clinical services at Waterstone Clinic and a general nurse and midwife. In her experience, Mary has found that awareness around fertility and fertility issues can be very mixed. “While there can be lots of information about fertility options and treatments, sometimes people are missing some important background and biological facts”.

Like many professionals in the field, Mary strongly feels that fertility and how it works should be information given to secondary school students. “There have been a lot of changes in the last ten years in both the junior and senior curriculums. More subjects like well-being are being added in, so there’s an opportunity to include areas like fertility. Young people hear about fertility in the media without much context, and these subjects could allow schools to offer age-appropriate fertility information right through school. Being informed and educated about their bodies and being aware of processes such as ovulation is important. That way, they can make good choices to protect their fertility because they will know that things like smoking, excess alcohol, drugs, STIs and extreme weight fluctuations can all be detrimental to fertility. It will help them not take it for granted.”

Mary firmly believes that the more facts you have at an early age, the better you can make informed decisions. She also believes the curriculum should give this information to all students, both male and female. “One of the reasons it’s essential not to leave men and boys out of this conversation is that fertility is not a women’s issue. Subfertility affects as many men as it does women, but men should also be aware of their partner’s fertility. Male fertility may not decline in the same way as female fertility, but their fertility is tied to their partner’s.”

Young people must understand “that they may not be super-fertile, and there is a possibility they may need help later. If you look at any class of first-year students, perhaps five or even more students sitting in that class will struggle to build their families in years to come and they may need some form of assistance when they’re older. The more that fertility is recognised – and that if you need it, support should be available to you – the more it becomes a central agenda, like other conditions or illnesses. Hopefully, then more information, education and health promotion will automatically follow.”

I ask Mary to list the top five pieces of information everyone should know when it comes to fertility. “What I would consider important in a fertility education course would be understanding your own body, the impact of age and lifestyle factors on fertility, and what kinds of things can damage it – even things like why boys shouldn’t keep laptops on their laps! That understanding can expand to predicting your most fertile times. Students could also benefit from discussing the signs you may need help and how talking to your family about their fertility can give you important information and clues to your own. Topics such as fertility preservation like egg freezing and the best age to carry that out, and the range of fertility treatments, stressing that IVF is not the only option if you need help conceiving.”

Bodily Autonomy

Professor Mary Wingfield is the clinical director of Merrion Fertility Clinic and a former consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at the National Maternity Hospital and St Michael’s Hospital Dublin. She is a founding member and past president of the Irish Fertility Society and served on the government-appointed Commission on Assisted Human Reproduction.

Professor Wingfield feels a lot of women don’t really have a solid understanding of just how much age affects their natural fertility, and also their chances of success with fertility treatment.

She also stresses that “in up to 50% of cases of subfertility, there is a male factor. In about a quarter of cases, it’s just the sperm that’s the issue, and in about half of cases, it’s a combination of male and female.” The third issue she feels people should be more aware of is the effect of body weight and obesity on fertility. “There is a link between being overweight and issues like polycystic ovaries, miscarriage and not ovulating. And then on the other hand, if a woman is very underweight, that can affect her fertility as well.”

Professor Wingfield agrees there’s huge room for improvement when it comes to overall awareness when it comes to fertility and that this is an important area that should be given adequate coverage in secondary school education, for both male and female students. “In Ireland, we’re way behind the rest of Europe in terms of anything to do with fertility. In the fertility Atlas published in December, Ireland ranked 40 out of 43 countries, and one of the things we were scored on was patient education and providing psychological support for people, and we scored very poorly when it comes to engaging the public in policy.”

“I think our whole society has drifted towards thinking that it is fine to start a family in your late thirties, early forties,” continues Professor Wingfield. “For young people in school or in college or who are starting out on their careers, when they’re planning their lives, it’s also important that they make fertility and having a family (if that’s what they want in the future) part of that plan. I would certainly like fertility to be part of the school curriculum, more awareness, more information leaflets produced by the Department of Health and sent out to GP surgeries and hospitals around the country so that it’s there for people to see, and education programmes for schools and GPs to discuss fertility with people as well.”

The key things Professor Wingfield believes everyone should know when it comes to fertility are “that a woman’s fertility really declines from age 30 on, so either they need to be thinking about getting pregnant then or if they’re not in a position to do that, in their early thirties, they should start thinking about maybe freezing eggs. Then how lifestyle affects fertility, not just in women but in men as well – obesity, diet, smoking, recreational drugs… For young men, if they have any issues with their testicles, they should go to their doctor… Safe sex is also a big thing – even if a woman is using the pill for contraception, she should be using condoms as well to prevent chlamydia and other STIs, which can cause damage to the fallopian tubes. Men should also be using condoms to avoid infections that can affect their sperm count. And people in same-sex relationships and transgender relationships should know there are options – for people who are transitioning, for instance, they may consider before they transition whether they want to freeze sperm or eggs in case they want to have their own biological children in the future.”

Professor Wingfield suggests another bonus to bringing fertility into the school curriculum: “More and more children who are going to school have been conceived through IVF. At least 3-5% of children now in Europe are born as a result of IVF and associated procedures. So even from that point of view, just making it more commonplace to talk about IVF and be aware of what IVF is, that it is a medical treatment that some people need will be of benefit.”

In the words of Malcolm X, “Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.” We must stop catering to the teenagers of today and start investing in the adult of tomorrow. Better awareness, better understanding leads to a better future for all.