By Holly O'Neill

17th Jun 2018

17th Jun 2018

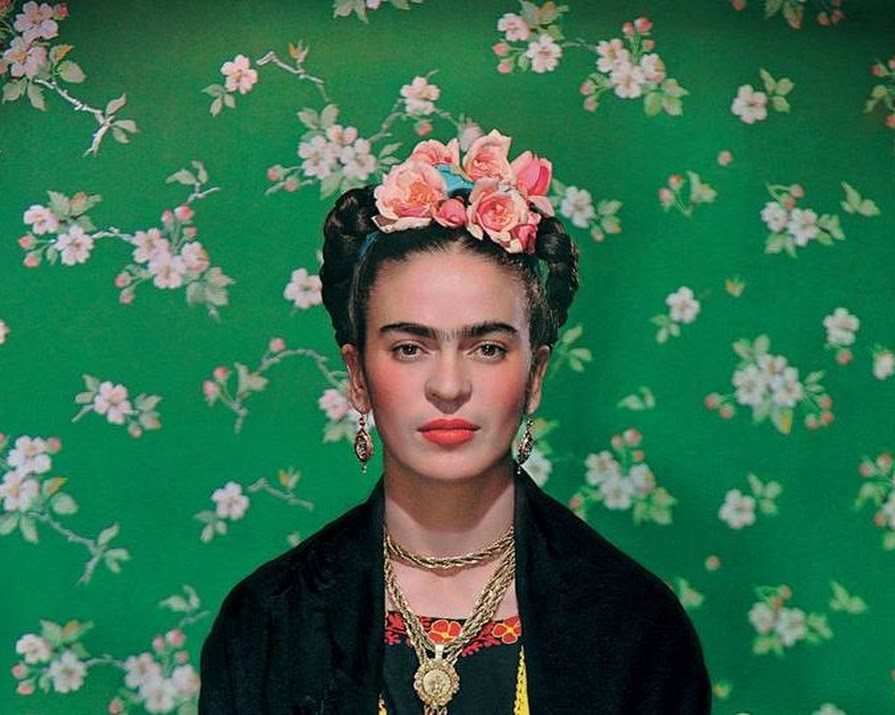

A collection of the artist Frida Kahlo’s personal possessions and beautiful clothing are exhibited in Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, from 16 June until 4 November. Some items in the collection have never been exhibited outside of Mexico, including her cosmetics.

In the collection, there are more than 200 items on display, from Frida Kahlo’s – full name Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón – iconic headpieces and Tehuana dresses, letters, pre-Columbian necklaces and prosthetics.

After the death of Frida Kahlo in 1954, her husband Diego Rivera, a famous muralist who was the great love of her life (despite extramarital affairs on both sides), shut her belongings in the bathroom of their house. The house was where Frida was born, had lived in with Rivero and died in, which was donated by Rivera in his will in order to later become The Blue House, also known as the Frida Kahlo Museum. Before his death, Rivera gave the keys of the bathroom to a friend and instructed the friend not to release the contents of the room until 15 years after Rivero’s death.

Nearly half a century later, the bathroom was opened, revealing thousands of hidden items including medicine, love letters from Frida Kahlo’s affairs and her perfectly preserved make-up bag. Historians spent four years cataloguing the contents – 6,000 photographs, 12,000 documents and 300 items, many of which are now on display in the V&A’s exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

A little backstory on Frida Kahlo’s life brings her appearance and artwork to life in a way you might not have appreciated it without knowing. Her life was changed irrevocably after contracting polio at six years old, meaning she spent the rest of her life in great pain, illustrated in many of her self-portraits including The Broken Column, 1944, which shows her spine as a crumbling column, nails penetrating every inch of her body and tears streaming down her face. At 18 years old, Frida Kahlo was in a bus accident where a handlebar impailed her through her pelvis into her womb and broke her spine. Her dreams of becoming a doctor had ended and her life shifted in an entirely new direction. While bedridden for months after the accident, Frida Kahlo started to paint. Her family placed a mirror on the ceiling above her in the hospital so she could draw herself and that’s when Frida Kahlo’s first self-portraits began.

Over her artistic career, self-portraits made up close to a third of Frida Kahlo’s artistic output. Her work inspired the next generation of female artists who, before Frida Kahlo, were not exploring themselves or their emotions in their art. Her work was surrealist, influenced by Mexican indigenous art, her mixed German-Mexican ancestry, her pain and the many roles she played in her life as an artist, lover, women and mother of all things. Her art considered an unfiltered view of the female experience, from objectivity to personal beauty and the implications that miscarriages had on her feminity – she connected herself through ribbons to all around her, from her many animals to tree roots, creating herself as a mother ‘of all things’.

Frida Kahlo, as a person, was an extension of the work she created. She transformed aspects of her appearance, drawing on her corsets and adorning her prosthetics – she had her leg amputated below the knee after contracting gangrene – and defined herself in her own terms, not allowing her disabilities define her.

Though she may have titled a self-portrait from 1933 as Very Ugly, (captioning it with, “Of my face, I like the eyebrows and the eyes. Aside from that, I like nothing. I have the moustache and in general the face of the opposite sex.”) Kahlo was a woman who spent a great deal of time curating her appearance. Every day she pulled her hair back, wove coloured scarves and floral corsages through it, and plaited it and pinned it up. She also wore a drawn on lip, warm powder blush and like to match orange or red nail varnish to her shawls.

Inside her make-up bag, and exhibited in the collection at the V&A, is Kahlo’s jar of Pond’s dry skin cream, a Revlon blush compact and powder puff in ‘Clear Red’, a collection of perfumes, Revlon lipstick in ‘Everything’s Rosy,’ Revlon nail varnishes, Chanel No.5 lotion, and in what may be the greatest discovery in the entire collection, the brow products. There was no foundation or concealer found, suggesting she preffered a natural complexion and no eye products. Of her brow products, there was a Revlon eyebrow pencil in the shade ‘Ebony’ and a product called Talika. Talika was reportedly was used to treat burns from soliders but also improved hair growth, which could imply that rather than dislike her unibrow or try to pluck it out, she worked her keep her unibrow looking thick and full.

Photograph Javier Hinojosa. Credit: © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives

In English zoologist, ethologist and surrealist painter Desmond Morris’ book, The Naked Woman: A Study of the Female Body, he writes of the unibrow, “to retain the sinister unibrow, a woman would have to be above fashion. That woman was Frida Kahlo, who wasn’t any more ashamed of her facial hair than she was of her infirm body. She made the single brow into a trademark detail of her self-portraits, in a calculated effort to tweak viewers’ assumptions about femininity and beauty.”

Frida Kahlo continues to draw in new fans, from feminists to women who have suffered miscarriages to anyone with a disability and as a result, with Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, the V&A has seen the most presales of any exhibition in the museum’s history.

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, sponsored by Grosvenor Britain & Ireland is at the V&A from 16 June – 4 November 2018, vam.ac.uk/FridaKahlo.

Featured image: Frida Kahlo on a bench, carbon print, 1938, photo by Nickolas Muray Credit: © The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Verge, Nickolas Muray Photo Archives