The rise of “underconsumption core” and “the anti-haul video” is an antidote to those who fell down the overconsumption rabbit hole, reminding the chronically online that hauls are far from normal, writes IMAGE.ie contributor Jenny Claffey.

I am a self-proclaimed YouTube fanatic, and what I watch on the platform has changed drastically over the years. For example, make-up tutorials used to bring me levels of comfort that I see others attribute to binging Gilmore Girls every autumn. I don’t know what it was about a 23-minute smokey eye tutorial that made me feel so zen, but watching a beauty influencer describe a cut crease for the 18th time brought me to an almost meditative state.

I don’t watch make-up tutorials any more, simply because I’ve watched so many that they’ve lost all meaning. Also, at 34, I feel I have my make-up routine down to a tee and want to keep it as simple as possible, so lengthy and complicated techniques don’t interest me anymore. When I was deep into my beauty YouTuber era though, I found myself so easily influenced that I had enough make-up to start a professional kit–and so, overwhelmed with products, I took a step back from the beauty world.

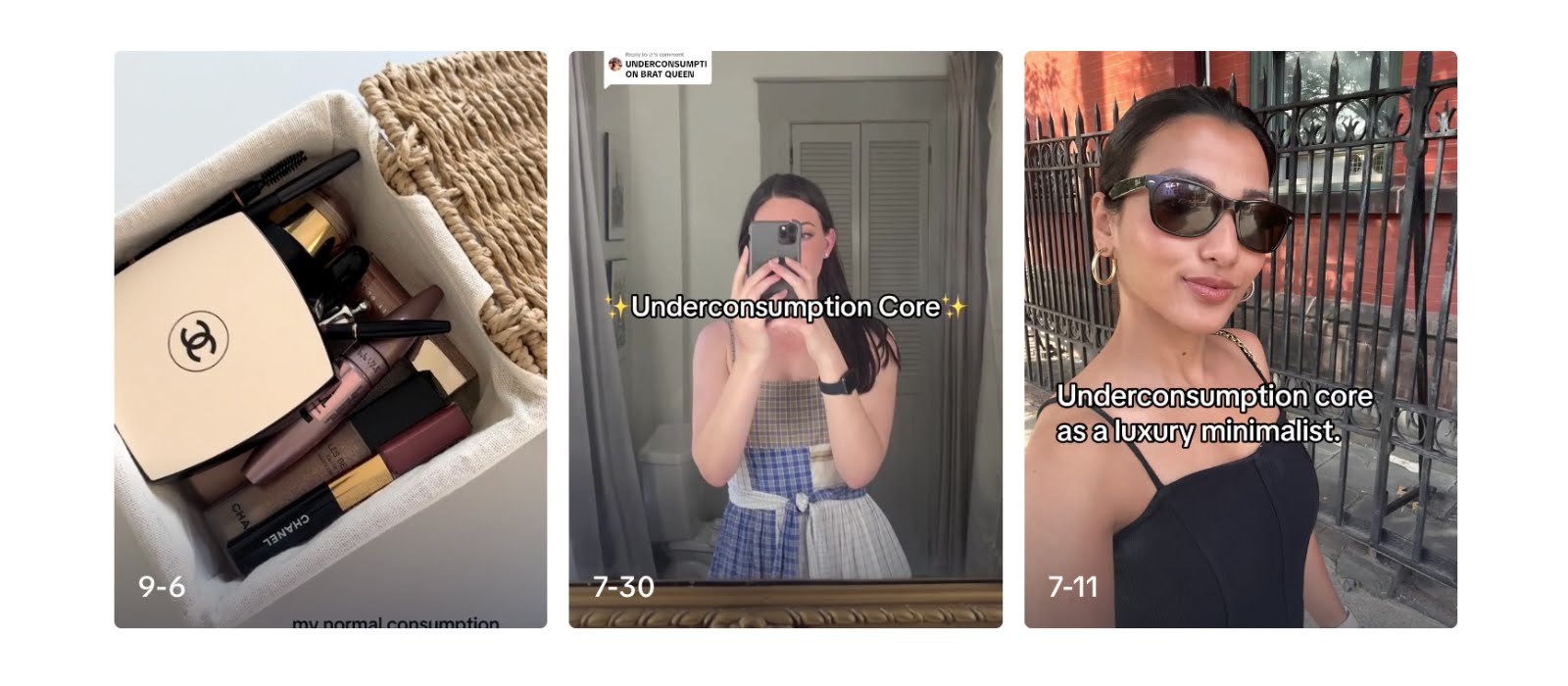

One YouTube genre I would attribute my reckless spending and make-up hoarding to is the ‘haul’ video. An influencer staple, hauls have likely inspired us all to make at least one regrettable purchase, and although still a popular style of video, lately, there has been some backlash–beginning with ‘anti-haul’ videos, and most recently with something known as “underconsumption core”.

An anti-haul video simply suggests what not to buy, but underconsumption core is different; rather than telling you what not to buy, it removes the idea of buying from the equation altogether. Underconsumption core is all about owning only what you need, rather than being guided by a compulsion to buy more.

See, hauls are much like mukbangs (videos showing a person eating a large quantity of food); the average person would probably never consume this much in real life, but watching someone else do it provides a level of escapism and maybe a touch of second-hand indulgence, but it also runs the risk of normalizing this level of mindless consumerism.

Search #underconsumptioncore on TikTok and you’ll find 4,500 videos where users show their 5-product make-up bag, shoes they’ve worn until they were unwearable, their single winter coat, a 3-step skincare routine and a capsule wardrobe. It may seem obvious to the few who escaped the ‘Haul Era’, but to those who fell down the overconsumption rabbit hole, a little show-and-tell can be a grounding force; reminding the chronically online that weekly hauls are far from normal.

The trend’s presence on TikTok is no coincidence, search #haul on the app and you’ll be shown 4.5 million videos, #makeuphaul has 255K entries and #clothinghaul has 490K. Despite conversations around sustainability, minimalism and ethical consumption being more present than ever online, it seems we’re still mesmerized by beautiful people showing us the beautiful things they’ve bought. Underconsumption core is a direct antidote to these videos.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, we were shopping online more than ever, maybe because we had nothing else to do, or spend our money on, but in March 2020 69% of internet users made an online purchase and 63% of those purchases were clothing and accessories. While “locked down”, we also turned to social media for our daily dopamine hit, finding escapism and social connection along the way; TikTok being the fastest-growing social media platform that year.

The world post-COVID feels very different, although online shopping is still on the rise, we have found ourselves in a cost-of-living crisis, a housing crisis and the ever-present climate crisis. With massive exposés on the fast-fashion industry that show us the true cost of our cheap clothes, paired with less disposable income, the allure of haul videos may be starting to wane. After years spent drowning in affiliate links, underconsumption core provides us with some much-needed respite; reminding us that is it not normal or necessary to buy so much.

Underconsumption core as a reaction to years of economic prosperity and consumerism reminds me of a theory known as The Hemline Index – which suggests skirt lengths rise or fall along with stock prices. According to this theory, the shorter the skirts, the stronger the economy but whether it’s true or not has been contested over the years. Hemlines don’t say much about the economy in the 2020s, seeing as women are no longer confined to wearing skirts and dresses and late-stage capitalism has made garment production cheaper than ever. However, how we respond to the very new industry of influencer marketing might be the best way to take the temperature in the room.

The rise of the modern-day influencer runs parallel to the economic recovery from the 2008 financial crisis–it wasn’t until 2013 that Ireland saw a decrease in unemployment year on year. As social media grew in popularity in the 2010s, and we entered into a new age of prosperity, showing off our purchases was a welcomed change of tone. It was under this new economy, that we welcomed the influencer to prosper.

Now that austerity is once again upon us, showing off our worldly possessions is no longer in vogue. Don’t get me wrong, the influencer industry is going nowhere, but what is changing is the kinds of content we are connecting to. It’s no longer sufficient for content creators to tell us what to buy, we also need to connect with them as a person.

We need to be careful in over-romanticising our underconsumption though, lest we fall into another trap. Although aestheticising consuming less is a net good, we have to remind ourselves that the first step in under-consumption is not changing what we buy, but not hitting ‘add-to-cart’ in the first place.

Watch on TikTok

As user @prettycritical on TikTok points out, changing our shopping habits is a lengthy process and it’s counterproductive to throw out what you have, so that you can buy more, to fit into a new aesthetic.

Photography by TikTok.